Bedřich Smetana

“Vltava” (“The Moldau”) from Má vlast

The Czech composer, conductor and critic Bedřich Smetana was born in Litomyšl on March 2, 1824 and died in Prague on May 12, 1884. Widely viewed as the most important Czech nationalist composers of the nineteenth century, he wrote eight operas, the most popular being The Bartered Bride (Prodaná nevěsta,1866). He is best known however, for his cycle of six symphonic poems, known as Má vlast (My Homeland, 1872-79), of which Vltava (The Moldau) is the most famous and frequently performed. Its premier took place on April 4, 1875 with Adolf Čech conducting. It is scored for piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (bass drum, cymbals, suspended cymbal, triangle), harp, and strings.

Every visitor to Prague carries away certain cherished memories of the many splendid vistas this magnificent city has to offer. One of my favorite venues is the ornate Karl’s Bridge that spans the Vltava (Moldau) River. The bridge itself, with its venerable history and statues, offers delights to the eye in every direction. One of the more romantic views is the one that is directed toward the ancient ruins of the castle Vyšehrad, by tradition a site that once served as the seat of the Kings of Bohemia. And if one is familiar with it, how can you fail at such a moment call to mind the majestic strains of Smetana’s music?

Vltava, or The Moldau as it is better known throughout the world, is the second of the cycle of six tone poems that comprise Má vlast (My Homeland). The composition of the cycle took place over a seven year span (1872-79), with Vltava appearing in 1874 (the same year, incidentally as another famous piece of eastern European nationalism—Mussorgsky’s mighty Pictures at an Exhibition). The conception of Má vlast, as well as some of its musical material, arose while the composer was at work on Libuše, a nationalistic opera. The six symphonic poems that comprise Má Vlast present, according to John Clapham in the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, a “conspectus of selected aspects of Czech legend, history and scenery.” The primary theme of the first poem, entitled Vyšehrad, is quoted toward the end of Vltava.

Smetana himself provided a kind of guide that leads the listener through the four principle sections of Vltava:

Two springs [depicted by flutes and clarinets] pour forth their streams in the shade of the Bohemian forest, the one warm and gushing, the other cold and tranquil. Their waves, joyfully flowing over rocky beds, unite and sparkle in the rays of the morning sun. The forest brook, rushing on, becomes the River Vltava (Moldau) [the memorable melody played by the strings]. Coursing through Bohemia’s valleys, it grows into a mighty stream. It flows through dense woods from which come joyous hunting sounds [fanfares in the brass section], and the notes of the hunter’s horn drawing ever nearer and nearer.

It flows through emerald meadows and lowlands, where a wedding feast is being celebrated with songs and dancing [duple meter Polka in strings and winds]. By night, in its glittering waves, wood and water nymphs hold their revels [shimmering tune played by strings and flutes]. And these waters reflect many a fortress and castle—witnesses of a bygone age of knightly splendor, and the martial glory of days that are no more. At the Rapids of the St. John the stream speeds on [reprise of Vltava main theme, followed by agitated full orchestra], winding its way through cataracts and hewing a path for its foaming waters through the rocky chasm into the broad riverbed [Main theme in the major mode], in which it flows on in majestic calm toward Prague, welcomed by the time-honored Vyšehrad [hymn-like appearance of theme from the first poem of Má vlast], to disappear in far distance from the poet’s gaze.

Much discussion has taken place about the origin and fate of the extraordinarily attractive principle theme of Vltava. Some have suggested that it comes from a Swedish folksong, which is possible since Smetana lived and worked in the late 1850s in Göteborg. Indeed, many Czechs know it as a folksong. Still others have noted the similarity of Hatikvah (The Hope), the unofficial national anthem of Israel, to this splendid tune, although the Encyclopaedia Judaica traces Hatikvah to a Rumanian folksong. The moral of the story here may be that we should beware of defining national musical themes in too narrow a fashion. After all, how many people realize that, despite its name, the Polka comes from Bohemia (Czech Lands), and not Poland?

Notes by David B. Levy, © 2003/2019

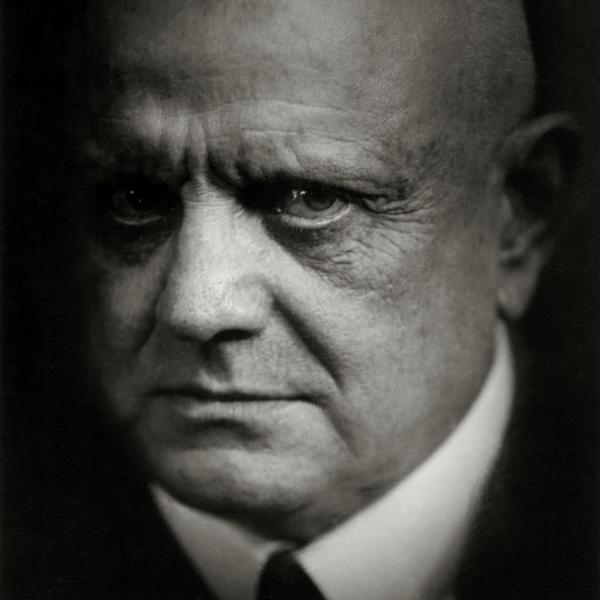

Jean Sibelius

Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 47

Jean Sibelius is indisputably the greatest composer Finland has ever produced. He was born on December 8, 1865 in Hämeenlinna (Tavastehus) and died in Järvenpää on September 20, 1957. His abiding interest in his homeland’s literature (especially the national epic known as the Kalevala) and natural landscape placed him in the vanguard of Finnish nationalism, although few traces of actual folk tunes are to be found in his music. Best known for his patriotic symphonic poem, Finlandia, Sibelius’s genius is revealed most clearly in his Violin Concerto and seven symphonies. His Violin Concerto was composed in 1903/04 and revised in 1905. Although intended for a Berlin premiere with Willy Burmeister as soloist, the original version of the Violin Concerto received its first performance on February 8, 1904 with Sibelius conducting and Victor Nováček, a violin teacher at the Helsinki Conservatory as soloist. For various reasons, not the least of which was Sibelius’s alcoholism, the premiere was a disaster. The premiere of the revised version took place in Berlin on October 19, 1905, with Karel Haliř as soloist and Richard Strauss conducting. The work is scored for solo violin, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, and strings.

Composed in 1903/04, but much revised in 1905, Sibelius’s Violin Concerto ranks as one of the greatest masterpieces of its kind, comparing favorably to those towering exemplars composed by Beethoven, Brahms, and Mendelssohn. The strong influence of the last composer mentioned may be seen most palpably in Sibelius’s first movement. Both works dispense with the traditional orchestral exposition and introduce the solo violin right away, in each case over a soft rippling figuration in the strings. A further similarity lies in the placement of the solo cadenza immediately before the recapitulation instead of at the end of the movement. Despite these structural similarities, the two works are quite different in temperament. Whereas Mendelssohn is typically lyrical, Sibelius is brooding, with his characteristic craggy orchestrations that favored cellos, basses, and bassoons to form the canvas upon which the solo violin paints its dramatic narrative. Another strong identifying characteristic is the way in which his themes emerge and grow, as it were, from the middle of each measure.

The powerful first movement is followed by a more lyrical and luxurious Adagio di molto. It begins with an unsettled figure in the woodwinds that will take on a more dramatic cast as the movement progresses. The violin solo then presents a broad and expansive melody. The passionate central section calls upon the violinist to play sophisticated cross-rhythms in double stops—another technique used by Mendelssohn in his own Violin Concerto.

The tempo indication of Allegro, ma non tanto (Lively, but not too much so) for the rondofinale needs to be taken at face value if the soloist hopes to finish the piece intact! The technical challenges for both the left hand and bow arm which the violin soloist must master are quite formidable and come in rapid fire. The opening theme has been described by Donald Francis Tovey as a “polonaise for polar bears.” But I can’t recall ever seeing these animals move at the speed at which Sibelius demands from his soloist. For all its fireworks, sheer technical dexterity is never evoked here for its own sake or for mere display. Passion also abides in this movement, as well as much evocative lyricism.

Program note by David B. Levy © 2012

Rachel Barton Pine performs Sibelius’s powerful Violin Concerto on these concerts. Learn about Rachel, view videos, find out about related events, and even hail a ride to the concert:

Info and Tickets

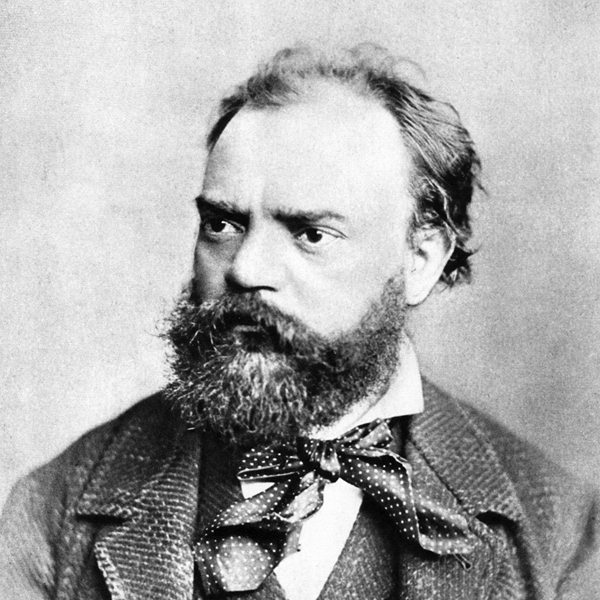

Antonín Dvořák

Symphony No. 6 in D Major, Op. 60

The Czech master Antonín Dvořák was born in Nelahozeves, near Kralupy, on September 8, 1841; and died in Prague, May 1, 1904. His Symphony no. 6 was composed between August and October 1880. The first performance was intended to be given by the Vienna Philharmonic under the baton of its dedicatee, Hans Richter. Because of anti-Czech intrigue, the premiere took place instead in Prague on March 25, 1881 with the Prague Philharmonic led by the composer’s friend, Adolf Čech. The work is scored for 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, and strings.

Throughout his career, Antonín Dvořák was facing a dilemma. Was he to become internationally identified as Antonín Dvořák the Czech composer, or as Anton, the Germanic European? Either way, his fame in Vienna was spreading rapidly, thanks largely to the efforts of Hans Richter, who was the principal conductor of both the Vienna Philharmonic and the Vienna Court Opera. The Czech lands, along with other nations that were under either German or Austrian hegemony, were asserting their independence and Dvořák knew that he could not stand idly on the sidelines. In addition to Richter, Dvořák enjoyed support in Vienna from Johannes Brahms, who secured performances and publications of his works throughout Germany and Austria. The Viennese audiences also seemed friendly to the Czech composer, as witnessed by the warm reception his Third Slavonic Rhapsody received in 1879. Unfortunately, however, many of the musicians who played in the Vienna Philharmonic and Court Opera, complained that Richter was programming far too many works by Dvořák and other Czech composers. To his credit, Richter never abandoned his advocacy of his Czech friend, conducting the Symphony no. 6 in London, which opened the door for the composition of his Symphony no. 7, which received its premiere in the British capital in 1885.

This, then, was the environment into which Dvořák’s Symphony no. 6 came into existence. A direct model for the new symphony was Brahms’s Symphony no. 2—a work that shares the same home key of D Major, as well as much of its idyllic charm. But just how “Czech” is Dvořák’s Seventh Symphony? In point of fact, nothing particularly reveals the composer’s nationality more than the lively Furiant third movement, the title of which is a Bohemian folk dance in triple meter that is filled with duple groupings that lend the piece its spice. Its minor-mode opening and alteration with the major mode provide additional color to this movement, as does the folksy use of the piccolo in the central trio section. But modal inflections and rhythms found throughout the work’s other movements bespeak those of the Czech language of folk idioms without actually quoting a specific folk melody. One particularly fine example is the theme that opens the symphony’s first movement—a lively thematic gesture that sticks in the memory of all who hear it. The work’s traditional four movements are filledwith sunshine and lyricism, combined with brilliant counterpoint and dance-like folk elements (scherzo).

Notes by David B. Levy © 2019