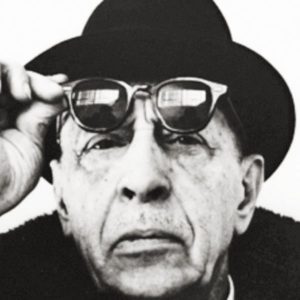

Igor Stravinsky:

Pulcinella Suite

One of the towering figures of twentieth-century music, Igor Stravinsky was born in Oranienbaum, Russia on June 17, 1882 and died in New York City on April 6, 1971. While his best known works remain the three ballet scores based on Russian themes and scenarios—The Firebird, Petrouchka, and The Rite of Spring—composed for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in the early 1910s, Stravinsky wrote works that encompass many genres and explore a wide variety of musical styles, all of which bear his own distinctive traits. His ballet, Pulcinella, was written for the Ballets Russes and is based on a play dating from the 18th century. It was first performed at the Paris Opera on May 15, 1920 under the baton of Ernest Ansermet. Pablo Picasso was both costume and set designer for the premiere. In 1922 the composer compiled the eight-movement Pulcinella Suite, which was premiered in Boston on December 22 of that year with Pierre Monteux directing the Boston Symphony Orchestra. He revised the Suite twice, in 1949 and again in 1965. It is scored for 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, trumpet, trombone, and strings (divided into a solo group comprising 2 violins, viola, cello, and contrabass and a larger ensemble).

What is it about clowns? Why, on the one hand, do they bring laughter and delight to many, while at the same time seem frightening and repulsive to others? What, indeed, lies behind that painted smile? Ever since the rise of the Commedia dell’ Arte in the sixteenth century we know the archetypical clown by many names: Pierrot, Polichinelle, Pedrolino, Pagliaccio, Puncinella, Punch, Petrouchka, Kasperle, to name but a few. In most cases the “sad clown” figure pursues, with no luck, the beautiful Columbine. His rival for her affections is the character, Harlequin.

In 1911, Igor Stravinsky, the Russian ex-patriot composer residing in Paris created a dazzling ballet for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes entitled Petrouchka (performed by the Winston-Salem Symphony in 2016). Still smitten with this Commedia dell’ Arte figure, Stravinsky in 1920 returned to a story involving the title character, now adopting the Italianate name of Pulcinella. This ballet score represented a new phase of Stravinsky’s style called neo-classicism. In this work the composer made modern adaptations of what he believed to have been melodies composed by Giovanni Battista Pergolesi (1710-36). It was later discovered that some of these pieces were from the pens of other, lesser known, composers. As Stravinsky wrote: “Pulcinella was my discovery of the past, the epiphany through which the whole of my late work became possible . . . but it was a look in the mirror, too.” Stravinsky’s “discovery of the past” was truly all encompassing, extending well beyond “neo-classical” to embrace the Renaissance, Baroque, and even Romantic eras. In the case of Pulcinella, unlike Petrouchka, the story ends happily for all its characters.

The eight movements that make up the Pulcinella Suite are delightful from start to finish. The mordant dryness of Stravinsky’s sharp rhythmic and metric style, so familiar from his earlier works, truly bring these 18th-century melodies into the 20th century in the most approachable manner. Recognizing that he had a “hit” on his hands, Stravinsky made further adaptations of excerpts from his ballet score, including two works entitled Suite italienne, respectively for violin and piano and cello and piano.

Program Note by David B. Levy, © 2018

Samuel Barber:

Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 14

The great American composer Samuel Osborne Barber was born in West Chester, PA on March 9, 1910 and died in New York City on January 23, 1981. A precocious talent from an early age, Barber demonstrated mastery as a composer during his studies at the then newly founded Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. His Concerto for Violin and Orchestra is in three movements and was composed between the summer of 1939 and July 1940. It received its first public performance on February 7, 1941, played by Albert Spalding with the Philadelphia Orchestra directed by Eugene Ormandy. It is scored for solo violin, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, snare drum, piano, and strings.

The story of the origin and compositional history of Samuel Barber’s Violin Concerto reads like a soap opera—literally. Its commission came from the laundry soap manufacturer, Samuel Fels (of the Fels Naptha fortune), whose adopted son, Iso (née Isaak) Briselli, was an accomplished violinist, born and schooled, along with many of the great violinists of the twentieth century (David and Igor Oistrakh, Nathan Milstein, Joseph Roisman, Dmitry Sitkovetsky, and others), in Ukrainian port city of Odessa. Barber was recommended to Fels by Gama Gilbert, a former violin student of the famous teacher, Carl Flesch. Fels offered Barber $1,000 for the concerto—a handsome sum in those days, with half to be paid down, and the other half to be paid upon delivery.

What happened next is shrouded in some mystery and controversy. Evidently, Briselli was very unhappy with the Presto in moto perpetuo final movement. Part of the controversy rests on the claim, once given common currency, that Briselli found the solo part of the finale “unplayable.” Another version has it that he found the movement to be too “light weight” in comparison to the first two movements. Yet another version suggests that he found the finale’s harmonies, shifting meters, and chromaticism too “modern” for his taste. Whether any of these stories is true may never be known, but thanks to Barbara Heyman’s authoritative biography of the composer, we can be sure that Briselli’s unhappiness was real enough, despite Barber’s attempts to demonstrate the movement’s playability and suitability. By this time, the composer began referring to his “concertino” as his concerto da sapone (a double-entendre, if ever there was one!). Briselli never performed “his” concerto, and the first public performance was given by Albert Spalding and the Philadelphia Orchestra (Eugene Ormandy conducting) on February 7, 1941, to great critical acclaim.

Despite its initial positive reviews, Barber’s Violin Concerto would have to wait a while before entering into the solo violinists’ core repertory. Among its most ardent champions have been Jaime Laredo and the late Isaac Stern. Many other major artists have made it a regular part of their concerto repertoire, much to their own delight, and that of audiences around the world. It has taken its place in history, not only as a wonderful example of Americana, but as one of the great violin concertos.

The first movement, Allegro, is a portrait of lyricism itself (Barber was an important composer of opera and vocal music). The romantic opening melody is joined with a whimsical quality brought about through a gentle concluding idea with its distinctive and unforgettable “scotch snap” (short-long) rhythm. While most of the movement is characterized by gentleness, pain too makes its appearance, especially at the start of the central development section. The Andante begins with a ravishing melody in the oboe (one might think of the second movement of Brahms’s Violin Concerto here). Modern audiences, upon hearing the finale, might well wonder what all the fuss was about. Its rapid-fire motion dispels the implied energy of the earlier movements, all the while giving the soloist ample challenges and opportunities for technical fireworks.

Notes by David B. Levy © 2006

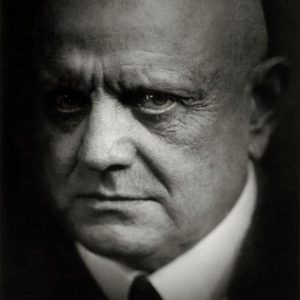

Jean Sibelius:

Symphony No. 1 in E minor, Op. 39

Jean Sibelius is indisputably the greatest composer Finland has ever produced. He was born on December 8, 1865 in Hämeenlinna (Tavastehus) and died in Järvenpää on September 20, 1957. His abiding interest in his homeland’s literature (especially the national epic known as the Kalevala) and natural landscape placed him in the vanguard of Finnish nationalism, although few traces of actual folk tunes are to be found in his music. Best known for his patriotic symphonic poem, Finlandia, Sibelius’s genius is revealed most clearly in his Violin Concerto and seven symphonies. The Symphony no. 1 was composed between 1898 and early 1899, but was revised in 1900 after Sibelius had directed the premiere. The earlier version does not survive and the revised (and only) version was premiered in Helsinki with Robert Kajanus leading the Helsinki Philharmonic on July 1, 1900. The work is scored for 2 flutes (both doubling on piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, and strings.

Some things are worth the wait. In the case of Sibelius, like Brahms, the world had to wait patiently for a First Symphony to appear. But once it did, the composer did not disappoint. This is not to say that Sibelius had no experience composing for orchestra prior to the completion of his First Symphony. Among its predecessors was En Saga (1892), the Karelia Overture and Suite (1893), the Lemminkäinen Suite (1896), and several other shorter works. His most famous work, Finlandia, was composed around the same time as the revised version of the Symphony no. 1. Having once studied in Vienna and living near the land of Tchaikovsky and Borodin, one can at times discern the influence of Anton Bruckner and the Russian masters. Bruckner is treasured for his magnificent writing for the brass section, and Sibelius proved every bit his equal.

Sibelius, when all is said and done, is a difficult composer to characterize. “Moody” might be the best word to describe his style, as he had an uncanny ability to go from folkish to craggy and exalted to melancholy, with the mere stroke of his pen. The wonderful thing about all this is his ability to make these changes of mood hold together as a logical entity. Those who love his popular Symphony no. 2 in D Major (1901-02), will be happy to know that the less frequently performed Symphony no. 1 contains the seeds from which the later work sprouted.

Cast in the traditional four movements, the first movement (Andante, ma non troppo; Allegro energico) opens with a haunting and melancholy solo for the clarinet, accompanied solely (at first) by the soft roll of the kettledrum. As the main body of the movement opens, we hear a remarkably bold and memorable theme—a sustained note followed by precipitous downward rush of energy. Although other themes emerge, this figure dominates the musical landscape of this opening movement. The second movement (Andante, ma non troppo lento) is marked by an overall sense of melancholy, albeit a lyrical one with moments of storminess.

The Scherzo: Allegro is a rousing affair, beginning with an insistent plucking of the strings. Again, like his older contemporary Bruckner, Sibelius excelled at writing exciting movements of this type. Here one is struck by the sudden changes of dynamics. Sibelius marked the Finale of his First Symphony Quasi una Fantasia: Andante—Allegro molto. The term “as if a fantasy” might bring Beethoven’s two Sonatas for Piano, op. 27 to mind (the more famous one being the so-called “Moonlight” Sonata). We should not look for musical similarities, however, as the term “Fantasia” implies a freedom of form and improvisatory spirit. The quiet clarinet theme that opened the first movement is given a new guise here, stated boldly by the strings. As the Finale moves ahead, new themes are presented, and the work ends as enigmatically as it began—full of Sibelian suprises and contrasts of mood.

Program note by David B. Levy, 2015