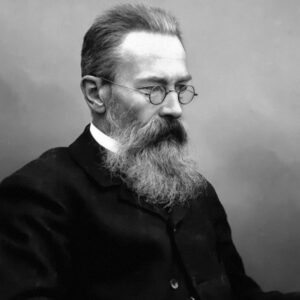

Béla Bartók

Concerto for Orchestra

One of the seminal figures of twentieth-century music, Béla Bartók was born in Nagyszentmiklós, Hungary (now Sînnicolau Mare, Rumania) on March 25, 1881 and died in New York City on September 26, 1945). In addition to his brilliant career as a composer, Bartók also was an important ethnomusicologist and pianist. His music is most strongly rooted in Eastern European folk idioms, merged with the modernisms of Debussy, Stravinsky, and Schoenberg and the disciplined structure of Johann Sebastian Bach. His Concerto for Orchestra was written in 1944 for the Koussevitzky Music Foundation in memory of Mrs. Natalie Koussevitzky. Its first performance took place on December 1, 1944 in New York’s Carnegie Hall with the Boston Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Sergey Koussevitzky. It is scored for 3 flutes (piccolo), 3 oboes (English horn), 3 clarinets (bass clarinet), 3 bassoons (contrabassoon), 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, 2 harps, and strings. The Winston-Salem Symphony‘s most recent performances of the Concerto for Orchestra were in February 2009.

The early months of 1943 found Bartók in poor health. Despite this, he managed to deliver three of six scheduled lectures at Harvard University. His hosts, however, insisted that he undergo a thorough physical examination, the results of which revealed a lung disease as well as other problems. ASCAP paid the expenses that enabled Bartók to enjoy a summer retreat at Saranac Lake, New York. Before the composer departed his New York City hospital, Sergey Koussevitzky tendered an offer of one thousand dollars from the Koussevitzky Foundation for a new work for orchestra that would honor the memory of the conductor’s wife who had died during the previous year. Had Bartók, ever wary of accepting charity, known that his fellow Hungarian violinist friend, Joseph Szigeti, had been an agent in procuring this commission, he might never have accepted it. As things stood, he was reluctant to accept the commission for fear that his poor health might prevent him from completing the work. Koussevitzky decided to offer Bartók an advance as a demonstration of good faith that the composer’s fears were unfounded. The resulting work, the Concerto for Orchestra, not only was completed, but has gone on to become one of the twentieth century’s greatest masterpieces. Its first performance took place on 1 December 1944 in Boston, with Koussevitzky directing the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

The title of this work requires some explanation. Bartók’s own program notes for its premiere indicated that the title “is explained by its tendency to treat the single orchestral instruments in a concertant or soloistic manner.” In other respects, the Concerto for Orchestra is as close as the composer ever came to composing a symphony. The work comprises five movements:

Introduzione. A slow theme based on the interval of the perfect fourth–an interval that will play an important role throughout the piece–is presented by the cellos and basses. As the music gains in speed and intensity, the flute, followed by three trumpets, introduce a new figure in the composer’s “parlando” (speaking) style. The tempo accelerates in dramatic fashion, leading to the main body of the movement, an Allegro vivace in sonata form. Two themes dominate through the remainder of the movement, the first of which has a dance-like character and metrical irregularity. The second idea is stated boldly by the trombone as a type of fanfare. Its potential for thematic manipulation is fully exploited by the entire brass section during the central development section. In an ingenious stroke, the movement ends triumphantly with a final statement of the fanfare theme.

Giuoco delle copie (Game of Pairs). This movement is the first of two scherzos. As a military drum sets the stage, instruments are paraded before us two by two, starting with bassoons, then followed by oboes, clarinets, flutes, and muted trumpets. Bartók adds a piquancy to this game by separating each pair of instruments by a set pitch interval. A chorale for the brass, accompanied by the ever-present parade drum, forms the central trio section of the scherzo. The game then resumes with the pairs returning in their original order, this time with the addition of counterpoint from the rest of the orchestra.

Elegia. Those who listen carefully will recognize that Bartók brings back the opening theme from the first movement here. This movement is dominated by a favorite device of the composer, an atmospheric “night” music created by string tremolos and glissandos in the harp and timpani. Other important thematic ideas are entrusted to the oboe and piccolo in this highly evocative movement.

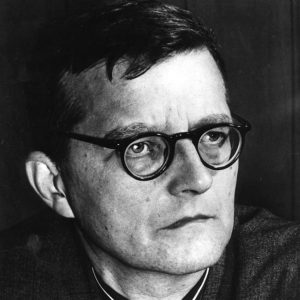

Intermezzo interotto (Interrupted Interlude). Koussevitzky was an admirer of the Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich. The conductor must have been a good sport to have toleterated this movement from the Concerto for Orchestra, since it mercilessly satirizes one of Shostakovich’s best-known themes. According to composer’s son Peter, Bartók heard a live radio broadcast of a performance of Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony (“Leningrad”) conducted by Arturo Toscanini. The martial theme from this piece’s first movement struck Bartók as particularly banal. The interlude in the Concerto for Orchestra begins with an agitated oboe solo, followed by a full-blooded romantic melody in the strings, akin to a Spanish serenade. The serenity of this tune is interrupted by the Shostakovich theme, which then becomes the object of Bartók’s delicious parody.

Finale. A cheeky theme in the horns paves the way for a whirlwind perpetual motion. The composer gives us little chance to catch our breath before he starts to spin a merry fugato based on the horn theme. The music retrenches momentarily, but then accelerates toward the entrance of the trumpet, who offers an appealing and triumphal new theme. The trumpeter’s colleagues in the brass section join in the exultation of the moment, presenting this new theme in both its original and an inverted shape. The strings and woodwinds take turns in offering a burlesque of the trumpet theme, but the movement’s recapitulation restores it to its original grandeur.

Notes by David B. Levy © 2008/2021