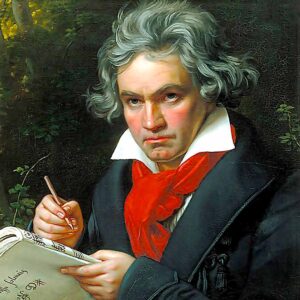

Ludwig van Beethoven:

Piano Concerto No. 1 in C Major, Op. 15

One of history’s pivotal composers, Ludwig van Beethoven was born on December 15 or 16, 1770 in Bonn, and died in Vienna on March 26, 1827. His Piano Concerto no. 1 was composed between the end of 1794 and the early months of 1795. The final and definitive version of the work was completed in 1800. The original version of Concerto may have received its first performance on March 29, 1795, on a concert of Vienna’s Academy of the Tonkünstler-Societät in the Hofburg Theater, although this concert may have featured the composer’s earlier Concerto in B-flat Major, Op. 19, known as the Concerto no. 2 due to its later publication date. It is far more likely that Op. 15 was first performed on December 18, 1795, at a concert arranged by Joseph Haydn in the Kleine Redoutensaal of the Habsburg Residence. The work is dedicated to Anna Luise Barbara, Princess of Erba-Odescalchi (née Keglevich), a student of Beethoven’s who also was the recipient of the dedication of his Piano Sonata no. 4, Op. 7. The Concerto is scored for solo piano, flute, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings. These performances mark the first in the Winston-Salem Symphony’s history.

The start to Beethoven’s career in Vienna in 1792 was a good one, with his reputation as a brilliant pianist and improviser preceding his arrival as a pupil of Joseph Haydn. His first two efforts in writing for piano and orchestra demonstrated clearly that he had learned well from the models offered by Mozart’s masterpieces of the 1780s. Mozart had long been Beethoven’s idol, the young musician having heard and performed many of Mozart’s works while still living in his native city of Bonn and playing viola in the Court Orchestra of neighboring Cologne. In fact, a piano score with orchestral cues exists for a Concerto in E-flat Major, WoO 4 dating from 1784, when Beethoven was only 14 years old.

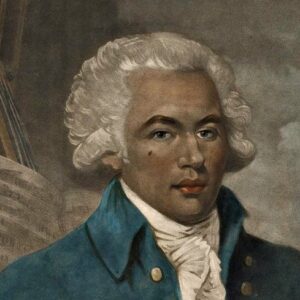

Terrence Wilson performs Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 1 on a program that includes music Seeger and Rachmaninoff, January 7 & 8, 2023.

The Piano Concertos, Opp. 15 and 19, original as they may be in certain respects, bear unmistakable signs of Mozart’s strong influence, and work on Op. 19 dates back to the years before he moved to Vienna. The Concerto we know as Concerto no. 1 in C Major may rightly be compared to Mozart’s Concerti, K. 467 and 503, both written in the same key and both of which contain openings of their respective first movements with a theme in the style of a march. It should come as no surprise that the young Beethoven, eager to impress his audiences, strove for a bolder and more expansive expression than that of his model. Offbeat accents were one way of distinguishing himself from Mozart, but even stronger evidence of this boldness lies in the way in which he presents the second theme in the remote key of E-flat, instead of the expected G Major. He eventually reaches that goal, but only after exploring the darker realm of G Minor. All of these elements and more are explored as we suddenly realize that 106 measures have transpired before the piano plays its first solo passage! The development section of this Allegro con brio first movement dwells in its own magical realm and illustrates Beethoven’s flawless sense of dramatic timing. The composer has also left us two fully composed cadenzas for the first movement, although he doubtlessly improvised one at its premiere.

The second movement, Largo, set in the unexpected and remote key of A-flat Major, begins with a lovely eight-measure song played by the soloist with only the gentlest of accompaniment from the strings. The writing for the wind instruments is limited to clarinets, bassoons, and horns, and offers the principal clarinet ample opportunity to shine. The finale, Rondo. Allegro, is a rambunctious affair, showing Beethoven in one of his “unbuttoned” moods of high spirits. Its opening theme, played by the piano alone, immediately grabs our attention and its high energy, even in the contrasting sections, never abates. Only towards the very end of the finale does the tempo slow down for a coaxing mini-cadenza which is answered by the solo oboe in an Adagio tempo. The pent-up energy is finally released as the full orchestra rushes, back in its original speed, toward the concerto’s final chords.

Program Note by David B. Levy, © 2022