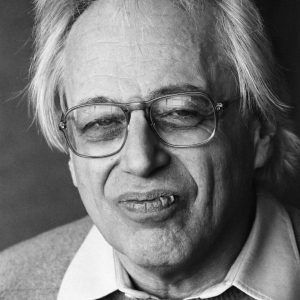

György Ligeti

Concert Românesc (Romanian Concerto)

Hungarian composer, György Ligeti, was born on May 28, 1923 in Transylvania, Romania and died in Vienna on June 12, 2006. Despite the locale of his birth, he is often identified as a Hungarian, as the region in which he was born was Hungarian-speaking and his family lived in Hungary when he was a child. His family boasted several musicians, the most famous of whom was his great uncle, the violinist Leopold Auer. Ligeti’s formal studies under Ferenc Farkas and others in Cluj and Budapest were interrupted because as a Jew, he was sent to a forced labor camp in 1943. After the war he became a member of the faculty of the Franz Liszt Academy in Budapest, but he escaped from Hungary after the 1956 revolution and settled in Austria. It is from these years that the Concert Românesc arose. Composed in 1951-2, the work did not receive its first performance until 1971. It is scored for 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, (2nd doubling English horn), 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 3 horns (3rd horn offstage), 2 trumpets, percussion, and strings.

Although audiences may not recognize the name György Ligeti, those who are fans of Stanley Kubrick’s films, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Eyes Wide Shut (1999) have heard his music. His opera, Le Grand Macabre (1974-77, rev. 1996), has been performed in recent years with greater frequency. A composer whose music covers many different genres, Ligeti’s earlier works reflect, not unlike Bartók and Kodály, the folk-like elements indigenous to Eastern Europe. Ligeti’s inclinations toward modern techniques were stifled by the communist regime in Hungary, so few of his more experimental works, such as Musica ricercata for solo piano (used in Eyes Wide Shut to great dramatic effect), remained “in the drawer” until a later date. His later works experiment boldly with tone clusters, microtones, and innovative choral and orchestral timbres.

Concert Românesc is a fine example of Ligeti’s folk style. He drew inspiration from childhood memories of the Carpathian Mountains, alphorn and peasant tunes, but the reactionaries of Hungary even considered his handling of them as too modern. The work comprises four movements, played without pause. The first movement, Larghetto, begins with a gentle rhapsodic tune in the strings. It links directly to the dance-like second movement (Allegro vivace), a vivacious affair filled with folk-inspired tunes clothed in colorful orchestrations. A single note hanging in the clarinet leads to the third movement, marked Adagio ma non troppo. A solo French horn imitates the calls of the alphorn, with responses coming from another horn located offstage. The solo English horn picks up the thread, accompanied by tremolando strings and the music picks up its intensity, leading to a lush statement in the strings before leading to mysterious figures in the winds and strings. The final movement, Presto poco sostenuto, opens with a bold announcement from the pair of trumpets. A rush of energy from the bottom to the top of the strings sets the mood for this whirlwind of a finale, which comes across as a kind of “Bela Bartók meets George Enescu” romp. The solo violin is put through its paces in this finale, which brings back a reminiscence of the horn calls from the third movement, before reaching its joyful conclusion.

Program Note by David B. Levy, © 2018

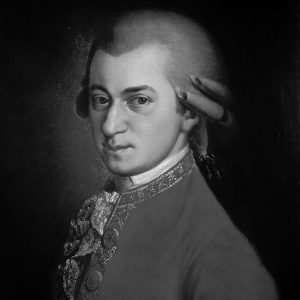

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Concerto No. 25 in C Major for Piano and Orchestra, K. 503

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was born January 27, 1756 in Salzburg. He died on December 5, 1791 in Vienna. The Concerto for Piano in C Major, K. 503 [no. 25], is dated December 4, 1786. It was probably composed for a series of Advent concerts in Vienna. The “K” number used for Mozart’s works refers to the name Ludwig Ritter von Köchel, who first issued the Chronological-Thematic Catalogue of the Complete Works of Wolfgang Amadé Mozart in 1862. The Köchel catalogue has been updated and revised many times to keep pace with musicological revelations. The work is scored for solo piano, flute, 2 oboes, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings.

Mozart’s interest in the genre of the piano (or rather, keyboard) concerto began when he was a mere twelve-year old who made arrangements of sonata movements by various composers. While many concertos were being composed in the mid-eighteenth century by an wide variety of German speaking and Italian composers, Mozart may have been most directly influenced by examples by Johann Christian Bach (1735-82), the youngest son of Johann Sebastian and half-brother to Carl Phillip Emanuel, himself the author of several concertos and one of the classic treatises on keyboard technique.

Mozart wrote 28 keyboard concertos throughout his life, in addition to isolated rondos and two concertos for two or three keyboard instruments. Of these, twenty-one of them are original and complete compositions. The fact that fully one third of these were published during the composer’s lifetime is the surest indicator of the success that these concertos enjoyed. The kind of piano for which Mozart composed is vastly different from the modern piano in many respects. Modern scholars often refer to this instrument as the fortepiano. More flexible in its dynamic range than the harpsichord, the fortepiano had an extremely light and fast action. The frame of the instrument was much smaller and was constructed mostly out of wood. The tone of the fortepiano decayed far more quickly than that of a modern piano. These instruments also were equipped to produce effects that simply do not exist on modern pianos. Achieving the proper balance between solo instrument and orchestra using modern instruments poses special challenges in this repertoire. Mozart’s concertos, however, like all works of transcendent genius, move and thrill audiences regardless of whatever tools are used in their transmission—be they replicas of Johann Walter fortepianos or modern Steinway grands.

This concerto is an excellent specimen of Mozart’s invaluable contribution to the genre. Cast in the traditional three movements, the first movement, Allegro maestoso, begins in the character of a fanfare (another hint that trumpets and timpani would not be out of place). The opening figure, which literally sounds like a knocking at the door, can be understood in a symbolic sense in that one can almost hear the approaching footsteps of the young Ludwig van Beethoven. Also notable is the exquisite scoring for the wind instruments. A secondary theme appears in the violins, whose opening could easily be mistaken for “Le Marseillais,” which is purely coincidental as Rouget de Lisle’s melody was not penned until 1792.

The second movement, Andante, in F Major evokes the eloquence of a Mozartean operatic aria. This is hardly surprising given that Mozart composed this concerto shortly after the completion of his incomparable opera buffa, Le nozze di Figaro. The finale is a sprightly rondo in duple meter whose opening theme is in the character of a gavotte, one of the most popular dances of the eighteenth century. Curiously there is no tempo indication in the sources, but it is often interpreted as Allegretto, i.e., a moderately lively speed befitting the character of its dance rhythm. Indeed, as Mozart scholar Neal Zaslaw has astutely observed, Mozart’s concertos for piano were indeed the “popular” entertainment of its time, and not viewed as “classics.” Modern audiences would do well to enjoy them in that same spirit.

Program Note by David B. Levy © 2018

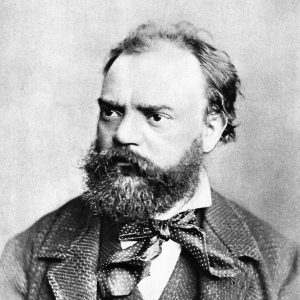

Antonín Dvořák

Symphony no. 8 in G Major, op. 88 (B. 163)

The Czech master Antonín Dvořák was born in Nelahozeves, near Kralupy, on September 8, 1841; and died in Prague, May 1, 1904. His Symphony no. 8 is one of his most popular works, yielding only to Symphony no. 9 (“From the New World”). It was composed in 1889 at Vysoká u Příbramě, Bohemia, on the occasion of his election to the Bohemian Academy of Science, Literature and Arts. Dvořák conducted its premiere in Prague on 2 February 1890. When first published, it was listed as Symphony no. 4. It is scored for 2 flutes (second doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, and strings.

One of Dvořák’s most popular and tuneful works, his Symphony no. 8 reflects a happy time in the composer’s life. The composer had experienced a rise to international prominence in the early 1880s, spurred in part by the skill he brought to bear in embracing the Bohemian nationalism established by his elder compatriot, Bedřich Smetana, but also by his growing mastery of form, harmony, and orchestration. Johannes Brahms stood at the forefront of Dvořák’s admirers, working actively to promote Dvořák’s music among German audiences and introducing the composer to the important music publisher, Simrock.

Dvořák, however, was torn between two worlds. How could he foster his acceptance outside of his homeland without sacrificing the folk-like elements of Czech music that had become an essential element in his emerging style? Anti-Czech sentiment in Vienna, the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire to which the Czech lands belonged, had been running high. A performance of Dvořák’s opera, Dimitrij, which had been a success in Prague, was now being contemplated for Vienna. But the directors of the opera house in Vienna decided that the staging of a Czech nationalistic opera was too risky, and pressure mounted for Dvořák to consider selecting from two German librettos for a new opera. To complicate matters further, Brahms was urging Dvořák to move to Vienna. Were Dvořák to accept these career moves, his future success would have been assured. The magnet of national identity proved too strong, however, and Dvořák respectfully declined the offer to compose the new opera. Thus freed, he turned his energies to other projects. The fact that these projects continued to include the composition of symphonies—nos. 7 (1885) and 8 (1889)—demonstrates that Dvořák could have things his way after all. The ongoing influence of Brahms’s symphonies, especially the Third Symphony (heard on the first concerts of this season’s Classics Series), had become reconciled with Dvořák’s Czech muse and he was now free to integrate his folk idiom into the structural rigors of symphonic composition. It is no accident that Dvořák’s best, and most popular, three symphonies—nos. 7, 8, and 9 (“From the New World”)—all came into being after the watershed events described above.

Dvořák’s Symphony no. 8 is, generally speaking, one of his most lyrical, and some writers have seen a kinship to the spirit of Beethoven’s “Pastoral” Symphony. The work is filled with fascinating innovations. Take, for example, the beautiful G-minor theme that begins the Allegro con brio first movement, a melody that presents itself softly and expressively in the clarinets, bassoons, horns, and lower strings, only to yield ground to the “real” first theme—a jaunty one with crisply dotted rhythms—chirped by the solo flute. The lyrical theme reappears at the start of the development section, and once again at the movement’s climax, now boldly blared by the trumpets against a tumultuous cascade of chromatic scales in the strings. The opening of the beautiful Adagio second movement in C minor shows how much Dvořák had learned from Brahms and Schubert. As in the first movement, Dvořák contrasts mellow timbres with brighter upper woodwinds. A haunting effect is created by the clarinets, who respond to each of the flute and oboe phrases with cadences that constantly shift modes. A contrasting major-key theme is introduced, punctuated by staccato chords in the brass and delicate scales in the violins.

The third movement, an Allegretto grazioso in G minor, features a graceful folk-like waltz theme. The three-part design introduces another lilting theme, this time in G major, as the central Trio section. An unusual coda follows the return of the opening section, in which the tempo shifts unexpectedly to Molto vivace and the meter changes from triple to duple. The symphony’s finale, which essentially presents a theme and variation structure, begins with a stirring and memorable fanfare introduction in the trumpets. The cellos then sing the principal theme, which is followed by a sequence of rather formal variations. This soon yields to an outburst of unbridled jubilation in the whole orchestra, highlighted by brilliant and raucous trills in the horns. Later in the movement we hear a quasi-serious march in C minor reminiscent of a rag-tag village band. The march becomes more assertive, subjected to a host of descending sequences, until the opening fanfare brings things down to earth. The variation theme returns, only to transform itself this time into a sublime reverie. The jubilant outburst returns, marking the onset of an exciting coda.

Program Note by David B. Levy © 1997/2018