Laura Karpman

All American

American composer, Laura Anne Karpman was born on March 1, 1959 in Los Angeles. Her formal musical education took place at the University of Michigan and the Juilliard School of Music. Among her many teachers were Nadia Boulanger, William Bolcom, Leslie Bassett, and Milton Babbitt. She is the owner of five Emmy Awards for her work in film, television, video games, theater, and concert music. Karpman has also received commissions from many noted artists and musical institutions throughout the world. A fierce advocate for women composers, she was the first woman to be inducted into the music branch of the Academy of Motion Pictures and Sciences. She also co-founded the Alliance for Women Film Composers in 2014. All American is the result of a commission from the Los Angeles Philharmonic and received its first performance at the Hollywood Bowl in 2019. It calls for a large orchestra that includes many unusual percussion instruments such as pots and pans, a butcher block struck with a meat tenderizer, and a Le Creuset braiser used as an anvil.

The origins of All American came from a commission by the Los Angeles Philharmonic for a short concert opener for a concert that included music by Charles Ives, Samuel Barber, and Duke Ellington. Laura Karpman’s initial reaction, according to an interview that appeared in the LA Times was “Great! We’ll call it ‘All American’ and I’ll figure out what to write later.” Her next instinct was to compose something patriotic, but upon further reflection, her womanhood, her sense of social justice, and her innate outspoken nature led her to create a mashup that would draw attention to the accomplishments of American female composers from the past.

These women, to Karpman’s way of thinking, were the shoulders upon which she herself was standing, but whose importance remained unrecognized by nearly everyone. Her research led her to the discovery of literally hundreds of compositions by American women. How many people know, for instance, that the melody of “Happy Birthday to You” was composed in 1912 by Mildred Hill (1859-1916)? This tune, along with Hill’s “March On, Brave Lads, March On!” makes an appearance in All American, along with Emily Wood Bower’s “Your Country Needs You,” and Anita Owen’s “’Neath the Flag of the Red, White, and Blue.”

As Laura Karpman wrote, “All American is dedicated to these women. Underneath these quotes is an uneven but propulsive rhythm and melody. For me, this is an analogy to women’s advancement, moving forward in a positive direction, but always with a little bit of a hiccup.”

Program Note by David B. Levy, © 2021

Felix Mendelssohn

Symphony No. 4 in A Major, Op. 90 “Italian”

(Jacob Ludwig) Felix Mendelssohn (-Bartholdy) was born, February 3, 1809 in Hamburg and died November 4, 1847 in Leipzig. Mendelssohn was one of the most important composers of symphonies in the first half of the 19th century. The “Italian” Symphony received its premiere May 13, 1833 in London under the baton of the composer. It is scored for 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings.

Of the five mature symphonies by Mendelssohn, the one designated as the fourth has proved to be the most popular with audiences and is the one that is most frequently performed. The “Italian” Symphony had its origins during Mendelssohn’s 1830-31 sojourn in Italy. It received its first performance in May 1833 in London with its composer, who also was one of the first renowned conductors, directing that city’s Philharmonic Society orchestra.

It may strike us as curious that the composition of this work was a difficult task for its brilliant young author, especially given the piece’s seemingly effortless melodic beauties and boundless energy. Mendelssohn grew up as a child prodigy, and he usually found composition to come to him with relative ease. But as he matured, Mendelssohn became more self-consciously aware of the work of other composers—both contemporaneous and from previous generations. This awareness led him to evaluate his own efforts with a more critical eye and ear. Throughout his life, Mendelssohn felt that the “Italian” Symphony was an imperfect work in need of revision. But for some reason—one suspects that his instincts overruled his intellect—he never revised the piece. The judgment of history has found the work to be a perfect specimen of its kind.

The first of the Symphony’s four movements is a brilliant Allegro vivace of high spirit. Among its arresting features are the rapid-fire woodwind chords that introduce, and subsequently accompany the first theme. The more solemn Andante con moto is alleged to have been inspired by a religious procession that the composer observed while in Naples. The stolid “walking” bass line and rapid changes of harmony give this movement a distinctly “Baroque” feel. This feature is not surprising in light of the composer’s life-long interest in the music of Bach, the culmination of which came in his landmark 1829 performance of the monumental Passion According to St. Matthew. The third movement of the “Italian” Symphony is marked Con moto moderato, and it follows the ternary design (A B A) characteristic of the traditional minuet and trio. The finale, marked Presto, is identified in the score as a saltarello—a leaping Italian dance. In point of fact, however, Mendelssohn makes use of two dances in this finale. The saltarello with which it opens is identifiable by its staccato articulation. The second dance, a tarantella, is uses the smoother legato (connected) articulation. A primary attraction of this movement is how skillfully the composer brings these dances together in counterpoint. A highly interesting and unusual feature of the finale is that it ends in the minor mode. One can identify any number of multi-movement works that begin in the minor mode and that end in the major. But to my knowledge, at least, the “Italian” Symphony is the only work that reverses this process.

Program Note by David B. Levy, © 1992/1997/2006/2018/2021

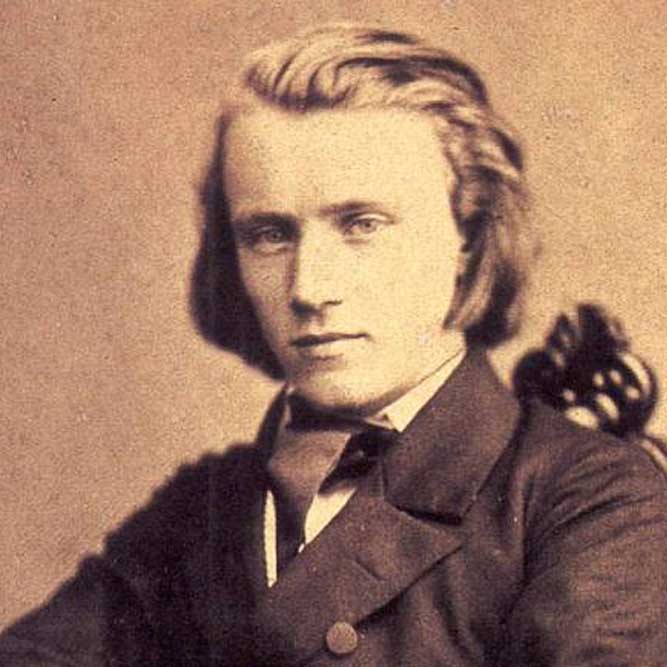

Johannes Brahms

Concerto No. 1 in D minor for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 15

Johannes Brahms was born on May 7, 1833 in Hamburg and died in Vienna on April 3, 1897. One of the dominant composers of the late nineteenth century, Brahms greatly enriched the repertory for piano, organ, chamber music, chorus, and orchestra. His Piano Concerto no. 1 was composed between 1854 and 1859 and received its first performance in Hanover on January 22, 1859 with the composer as soloist and the orchestra led by Joseph Joachim. It is scored for solo piano, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings.

The first of Brahms’s two concertos for piano and orchestra was first performed by the composer with Joseph Joachim conducting in Hanover on January 22, 1859. The work’s immense size and great intensity of expression reveal the composer’s original plan for much of its thematic material—a symphony. The Piano Concerto in D Minor is, indeed, symphonic in its proportions.

The work first began to emerge in 1854, in which year the young composer conceived of a sonata for two pianos. The next five years found the work and its composer underwent profound changes—from both a personal and professional standpoint. These years were significant ones in Brahms’s complex relationship with Robert and Clara Schumann. In 1853, Robert Schumann had symbolically performed a “laying of hands” upon Brahms’s head by means of a lead article, “Neue Bahnen” (“New Paths”) published in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (an important periodical founded by the Schumann in 1834). The article points to the twenty-year-old Brahms as the true heir and custodian of the heritage of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, and Schumann himself. Schumann’s public endorsement proved to be a mixed blessing for Brahms. What if he should fail to measure up to the promise?

In February of 1854, Schumann attempted suicide by throwing himself into the Rhein, leading to two-and-a-half years of hospitalization for mental illness. During this disturbing period, Brahms remained loyal to Schumann, but also found himself becoming emotionally involved with Clara. All of these external biographical events surely played a role in Brahms’s emerging concepts for his concerto. The absorption of Beethoven’s models—the Ninth Symphony and Third Piano Concerto most especially—were no less important factors.

The center of gravity of this concerto lies in its immense opening movement (Maestoso). Those familiar with the first movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony (in the same key of D Minor) will recognize the influence that mighty work is exerting here. The first movement of the concerto follows the traditional classical form for the first movement of such works, but in this case the themes are especially luxurious, expansive, and dramatic. The piano writing is technically challenging, replete with triple trills and sophisticated metrical patterns. Virtuosity, however, never overshadows the music’s expressive power. If the work may be said to have any flaws, it would be that its ideas are greater than the inexperienced composer’s ability to handle them, especially from the standpoint of orchestration.

The Adagio offers welcome relief from the torment of the first movement through its contrast of D Major to the previous D Minor, its hymn-like themes, and muted strings. The finale is an energetic and dramatic Rondo (Allegro non troppo), whose main theme is marked by its syncopated rhythms and boundless energy. Again the influence of Beethoven is apparent. The listener will note that is Brahms’s theme and its accompaniment are closely modeled after the finale of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto no. 3 in C Minor. Perhaps Schumann was correct in placing Beethoven’s mantle on Brahms’s shoulders.

Program Note by David B. Levy © 2010/2021