Dan Locklair

In Memory—H.H.L.

The following program notes by the composer are taken from his website (www.locklair.com):

“The primary musical material for this short, single movement elegiac composition comes from the plagal cadence (IV-I). Since this cadence is often associated with the close of hymns on the word “amen,” it has often been referred to as “the amen cadence.” The finality of the word “amen” (meaning “may it be so”) to a prayer or a hymn that is a prayer, seemed to me a most appropriate symbol of musical remembrance for the finality of my mother’s earthly life. Further, a church school teacher of two-year-old children for many years, Hester Locklair always taught her classes a simple pentatonic hymn, Jesus Loves Me. Paying tribute to that, a brief quote from that hymn (played pizzicato by the violas) is heard near the end of In Memory – H.H.L.”

The work has been recorded on the Naxos label with Kirk Trevor leading the Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra. Maestro Trevor had the following to say about In Memory – H.H.L.:

“After the first read-through of In Memory – H.H.L. I realized we had found a worthy successor to the Barber Adagio. Here was a gorgeously crafted adagio for strings that had a new voice, but with the same hauntingly lush harmonies and intensity that makes the string orchestra such a beautiful vehicle in the concert hall. After recording it, I was even more convinced that In Memory – H.H.L. has a real place in the standard string orchestra literature. As a conductor we are often looking for that five minute adagio to fit into our programming, and now we have a second option to the Barber from a wonderful living American composer.”

Notes by David B. Levy/Dan Locklair, 2020

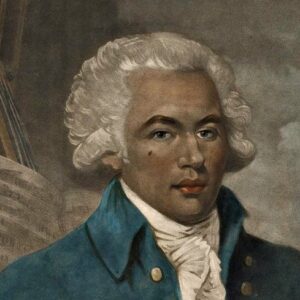

Aaron Copland

Appalachian Spring

Aaron Copland was born in Brooklyn, NY on November 14, 1900, and died in North Tarrytown, NY on December 2, 1990. In addition to his distinguished accomplishments as a composer, he was an important author on musical topics, as well as a gifted pianist and conductor. Furthermore, he was a mentor to at least two generations of important American composers. Copland, more than any composer in the 20th century, gave classical music a distinctly “American” voice. His score for Martha Graham’s ballet, Appalachian Spring, dates from 1943 in its original version for thirteen instruments. The first performance of the original score took place on October 30, 1944. He later expanded the orchestration and extracted a suite for full orchestra in 1945. The first performance took place on October 4, 1945 with Artur Rodzinski conducting the New York Philharmonic. The most recent performance of the expanded orchestration by the Winston-Salem Symphony took place in April, 2016 under the baton of Robert Moody. The original version was last performed at the Blue Ridge Performing Arts Center in Galax, VA conducted by Assistant Conductor, Jessica Morel. This orchestration calls for flute, clarinet, bassoon, piano, 4 violins, 2 violas, 2 cellos, and bass.

My mentor, the late Professor Charles Warren Fox of the Eastman School of Music, liked to share the following story. Aaron Copland was approached by an admirer who, after hearing a performance of his ballet, Appalachian Spring, insisted that its music evoked in the listener’s mind an accurate musical image of the Appalachian mountain chain, one that could never be confused with an image of the Rockies, Cascades, Alps, or any other chain. Copland politely responded by telling how, after putting the finishing touches on the score, he approached choreographer Martha Graham with the following query: “Oh Martha, what are we calling this ballet I just composed?” Fox’s story may be apocryphal, but it serves as a warning to avoid imposing too specific an interpretation on any piece of instrumental music. Regardless of which mountain chain (and, I might add, what pronunciation of its name!) Copland and Graham may have had in mind, we can rest assured that Appalachian Spring is one of the true masterpieces of twentieth-century music—American or otherwise.

According the Graham, she conceived the ballet as “a pioneer celebration in spring around a newly built farmhouse in the Pennsylvania hills in the early part of the [nineteenth] century.” Copland, speaking about his music for Appalachian Spring, observed that it was “generally thought to be folk inspired,” but added quickly that the Shaker tune, “Tis the Gift to be Simple” was the work’s only actual folk quotation. The composer’s decision to alter his style in this work from an angular modernist idiom to one more audience-friendly was both deliberate and courageous. Copland’s new style, as exhibited in Appalachian Spring, relies on idiosyncratic and characteristic harmonic vocabulary (based largely on widely-spaced chord formations that take the edge off its dissonance) and Stravinskian rhythmic subtlety and drive learned in Paris during his period of study in that city with Nadia Boulanger.

Originally scored for thirteen instruments and first performed at the Library of Congress on October 20, 1943, Copland subsequently arranged Appalachian Spring into a concert suite for full orchestra in 1945. It falls into several clearly articulated sections, beginning quietly with hushed chords and lovely touches of orchestration in the winds, harp, and solo violin. The next section introduces a lively (square) dance, full of piquant stops and starts. It is intended to depict the “bride-to-be and the young farmer [enacting] the emotions, joyful and apprehensive, their new domestic partnership invited.” A wonderful hymn in slower note values emerges in the woodwinds as a splendid counterpoint to the vigorous dance. The next section presents a gentler dance, followed by a slower, more intensely contemplative scenario—perhaps intended to display the couples’ apprehensions. A new, even more energetic dance with humorous rhythmic punctuations at the end of each measure, follows. This mood is interrupted abruptly, if briefly, by the full orchestra, but yields once again to yet another whirlwind dance. This too subsides the music harkens back to the hymn that we heard a few moments earlier. The sound-world of ballet’s opening now prepares the way for Copland’s quotation of the Shaker hymn and its variations:

‘Tis the gift to be simple,

‘tis the gift to be free,

‘Tis the gift to come down

where you ought to be,

And when we find ourselves

In the place just right

‘Twill be in the valley of

love and delight . . .

When true simplicity is gained

To bow and to bend we

shan’t be ashamed,

Turn, turn will be our delight,

Till by turning, turning

we come round right.

The suite closes in hushed tones reminiscent of a gentle benediction and emblematic of the evening twilight’s fall as the young couple prepare to begin their new life together.

Program Note by David B. Levy, © 2001/2015/2020

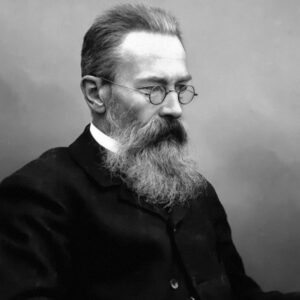

Antonín Dvořák

Serenade for Strings

The Czech master Antonín Dvořák was born inNelahozeves, near Kralupy, on September 8, 1841; and died in Prague, May 1, 1904. His Serenade for Strings was composed in 1875 and received its first performance took place in Prague on December 10, 1876 with Adolf Čech directing the orchestras of the Czech and German theatres. Emanuel Starý made an arrangement of the piece which was published in Prague in 1877. The score of the original version appeared in print in Berlin two years later. The Serenade’s scoring calls for violins, violas, cellos, and bass.

Dvořák’s five-movement Serenade for Strings stands among the composer’s most popular works. While not as frequently performed by orchestras as his last four symphonies of the magnificent Concerto for Violoncello and Orchestra, its hearing on concert programs is always welcome. The work also has been overshadowed—unfairly, one might add—by Tchaikovsky’s work of the same name, composed five years later. Often a composer’s greatest compositional skill is hidden by the seeming simplicity of a given musical work. Surely this is the case in Dvořák’s lovely work, a companion of sorts to his Serenade for Winds in D Minor, Op. 44, composed three years later (1878).

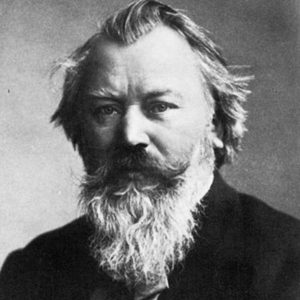

The composer dashed off this delightful work in short order in May of 1875. He was by then married, expecting his first child. But his financial situation was not good, as evidenced by a letter of recommendation written by none other than Johannes Brahms to his publisher Simrock in Berlin penned two years later:

As for the state stipendium, for several years I have enjoyed works sent in by Antonín Dvořák (pronounced Dvorschak) of Prague. This year he has sent works including a volume of 10 duets for two sopranos and piano, which seem to me very pretty, and a practical proposition for publishing. … Play them through and you will like them as much as I do. As a publisher, you will be particularly pleased with their piquancy. … Dvořák has written all manner of things: operas (Czech), symphonies, quartets, piano pieces. In any case, he is a very talented man. Moreover, he is poor! I ask you to think about it! The duets will show you what I mean, and could be a ‘good article’.

Brahms was to become one of Dvořák’s most enthusiastic advocates.

Dvořák was a violist who knew the capabilities of string instruments and their sonority very well. One would be hard-pressed to find a more amiable first movement than the lovely Moderato that opens the work. It begins with a gentle dialogue between the first violins and cellos. The return of the opening material is gracefully embellished, with the texture thickened by dividing the violin, viola, and cello lines into parts (divisi). Dvořák continues to divide the strings in this fashion throughout the entire work.

The second movement, Tempo di valse, is perhaps the best-known of the work’s five movements. Structured like a minuet or scherzo, it features a contrasting “trio” section sandwiched between the wistfully melancholic waltz theme in C-sharp minor.

The third movement is a duple-meter scherzo of great energy. This Vivace escapade changes mood frequently. Towards the end, the composer slows the tempo before a sudden final outburst of energy. It is entirely possible that this gesture was inspired by the final movement of Beethoven’s String Quartet in F Major, Op. 59, no. 1 (“Razumovsky”), which coincidentally (?) is in the same key.

The emotional heart of Dvořák’s Serenade is to found in the Larghetto fourth movement, with its achingly beautiful melodies, treated in canonic fashion, as well as its lush harmonies and texture. Astute listeners will detect that the composer brings back one of the themes from the second movement. The Finale: Allegro vivace is a folksy and rigorous affair marked by many unexpected and tricky rhythmic displacements. On hearing the opening, one might conclude that the movement is in the minor mode, but this is but a feint that yields to unbridled fun and joviality. A particularly poignant moment comes when Dvořák brings back the main theme of the work’s first movement, only set the stage for a brilliant rush to the end.

Program Note by David B. Levy © 2020