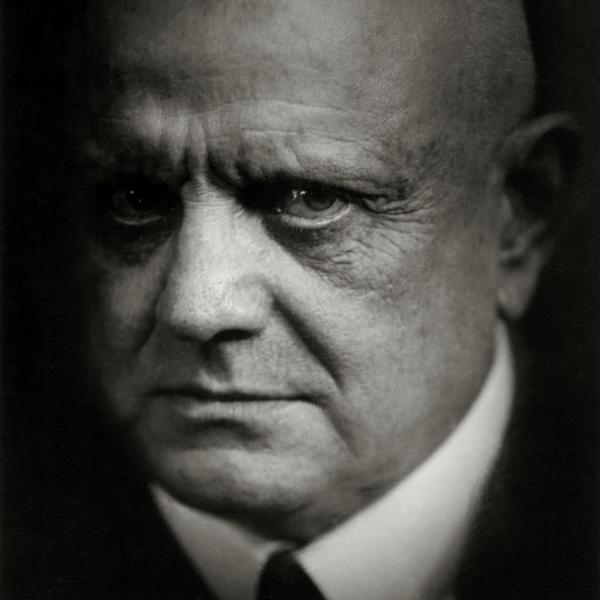

Jean Sibelius:

Symphony No. 7 in C Major, Op. 105

Jean Sibelius is undisputably the greatest composer Finland has ever produced. He was born on December 8, 1865 in Hämeenlinna (Tavastehus), Finland and died in Järvenpää, Finland on September 20, 1957. His abiding interest in Finland’s literature (especially the national epic known as the Kalevala) and natural landscape place him in the forefront of Finnish nationalism, although few traces of actual folk tunes are to be found in his music. Best known for his patriotic symphonic poem, Finlandia, Sibelius’ genius is revealed most clearly in his Violin Concerto and seven symphonies, of which the Second and Fifth Symphonies are most frequently performed. His Symphony no. 7 was the last one he completed and dates from 1924. We know that he had worked on an Eighth Symphony, but he destroyed the manuscript for it in 1940. When The Seventh was first performed on March 2 of that year in Stockholm, it was identified as Fantasia sinfonica no. 1. Only later did the composer decide to rename it when it was published the following year. The work comprises many sections which are played without interruption and is scored for 2 flutes (doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, and strings.

Sibelius rarely got things “right” on the first try, and it became one of his habits to revise his compositions. One may further assert that Sibelius’ entire output as a composer of symphonies was one uninterrupted search for an ultimate “solution” to the challenge of writing a symphony. Some analysts and historians have suggested that his Seventh Symphony, composed in one continuous movement, gives ideal expression to the concept of unification of symphonic logic, or as Robert Layton states in his biographical essay on the composer in the New Grove Dictionary:

The Seventh Symphony came as the climax of a lifetime’s work: it has the effect of a constantly growing entity, in which the thematic metamorphosis works at such a level of sophistication that a listener is barely aware of it. In its degree of organic integration and thematic working, the piece stands at the peak of the symphonic tradition.

New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians

Indeed, organic is an apt way of describing much of Sibelius’ music. Each musical event seems to emerge, as if in midstream, out of the solid earth of his musical imagination, as well as the building blocks of his orchestration—a feature that treats the brass, winds, and strings as individually sonorous wellsprings. Sibelius himself revealed as early as December of 1917 that he had “in my head” ideas for his Sixth and Seventh Symphony.

The Seventh Symphony can be said to have three principal sections (Adagio, Vivacissimo, and Allegro moderato), with many changes of tempo serving as sinew holding the basic structure together. Of special importance is a magisterial thematic statement in the solo trombone, which may be said to be the symphony’s main theme.

Program Note by David B. Levy, © 2021

Ralph Vaughan Williams:

The Lark Ascending

Ralph Vaughan Williams, one of England’s most important composers of the early 20th century, was born in Down Ampney, Gloucestershire on October 12, 1872 and died in London on August 26, 1958. A composer of wide range, his output included nine symphonies, other works for orchestra and band, film scores, songs, operas, and several choral pieces. The Lark Ascending was originally composed for violin and piano in 1914, although it was not performed until 1920, the same year as the version for violin and orchestra was created. The orchestral version was first performed in the Queen’s Hall on June 14, 1921 with Sir Adrian Boult conducting and Geoffrey Mendham as soloist. The work is dedicated to the British violinist, Marie Hall.

Ralph Vaughan Williams subtitled The Lark Ascending a “Romance,” much in the same spirit as Beethoven had created two Romances for Violin and Orchestra (Op. 40 and 50, respectively). Closer to Vaughan Williams’s own time, the Czech master, Antonín Dvořák, composed a Romance for Violin (1873) that exists, like The Lark Ascending, in two versions. Vaughan Williams was himself a violinist, which enabled him to write exquisitely for his instrument. Understandably, the work has become a favorite of violinists everywhere and has been recorded by many artists. While especially popular in England, the work is beloved throughout the musical world.

This achingly beautiful and pastoral composition is based on a poem of the same name by the English novelist and poet, George Meredith (1828-1909). According to the composer’s wife, Ursula, the composer had “taken a literary idea on which to build his musical thought . . . and had made the violin become both the bird’s song and its flight, being rather than illustrating the poem from which the title was taken.” The original poem is quite long (122 lines), but Vaughan Williams chose the following twelve to place at the head of his score:

He rises and begins to round,

He drops the silver chain of sound

Of many links without a break,

In chirrup, whistle, slur and shake.

For singing till his heaven fills,

’Tis love of earth that he instils,

And ever winging up and up,

Our valley is his golden cup,

And he the wine which overflows

To lift us with him as he goes.

Till lost on his aërial rings

In light, and then the fancy sings.

The surface simplicity of The Lark Ascending belies its underlying sophistication. A product of the era of the First World War, its pastoral nature, abetted by folk-like modal inflections, lends the work a wistful melancholy, while at the same time enchanting the ear with sounds of solace.

Program Note by David B. Levy, © 2021

Margaret Sandresky:

Gaudeamus

One hundred years young, Margaret Vardell Sandresky was born April 28, 1921, in Macon, Georgia. She was the daughter of Eleanor Ferrill, a gifted soprano, and Charles Gildersleeve Vardell, a well-known pianist, organist, and composer. Her family moved to Winston-Salem, North Carolina, in 1923, when her father joined the faculty of Salem College School of Music. There she remained until her graduation in organ from that school in 1942. She earned a Master of Music degree in composition at the Eastman School of Music in 1944, where she studied organ with Harold Gleason, and composition with Howard Hanson and Bernard Rogers. In 1955, she was awarded a Fulbright grant to study organ in Frankfurt, Germany with Helmut. Upon her return she married Clemens Sandresky, pianist and dean of the School of Music at Salem College. After teaching music theory at Oberlin Conservatory of Music and the University of Texas at Austin, she returned to Salem College, where she taught until her retirement in 1986. Additionally, as a founding member of the faculty of the (University of) North Carolina School of the Arts, where she established its organ department in 1965. Gaudeamus, composed in 2020, was written in celebration of Salem Academy and College, “Empowering Women for 250 Years.” The work is the result of a joint commission from Salem Academy and College and the Winston-Salem Symphony Association, Inc. It is scored for 2 flutes (piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, harp, and strings.

Gaudeamus holds an honored place as a composition in celebration of institutions of learning, such as Johannes Brahms’ Academic Festival Overture (University of Breslau [now Wroclaw]) and Benjamin Britten’s Cantata Academica (University of Basel). This one-movement work is ushered in by a noble fanfare in the trumpets with responses resounding from the rest of the orchestra. It soon introduces the chorale melody, “Nun danket alle Gott” (Now thank we all our God), which the composer revealed to this writer in an interview conducted in early June, is not the progenitor of the thematic material of the work, but instead refers to the Moravian tradition of singing this chorale upon the completion of a new building.

The arrival of such a auspicious occasion as the 250th anniversary of the founding of a remarkable educational institution as Salem Academy and College, nourished in rich Moravian soil, but ever looking toward the future, Sandresky has created a new work that reflects the deep love and respect she holds for a place that has been such an important part of her life and career. Salem Academy and College is treasured by all of her alumnae, as well as standing as a source of pride and inspiration for our entire community.

Program Note by David B. Levy, © 2021

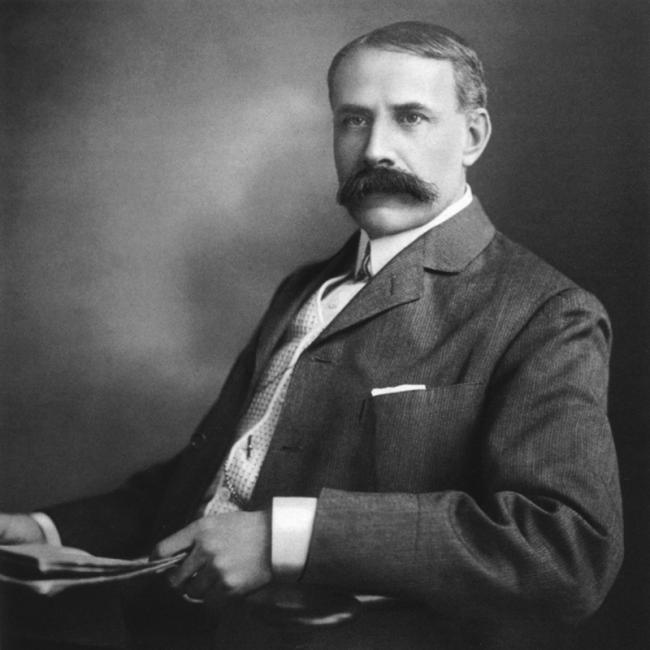

Edward Elgar:

“Enigma” Variations, Op. 36

Sir Edward Elgar was born in Broadheath, near Worcester, on June 2, 1857 and died in Worcester on February 23, 1934. He is arguably the finest English composer of his generation and ranks as a true master. He contributed a large amount of music to a variety of genres (except opera). His symphonic works include two symphonies, concertos and most famously, his Enigma Variations. The work was composed in 1898-9 and its premiere took place conducted by Hans Richter in London’s St James’s Hall on June 19, 1899. A version with extended finale was conducted by Elgar himself at the Worcester Festival on September 13, 1899. The work is scored for 2 flutes (one doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, organ (ad lib) and strings.

Elgar’s Variations on an Original Theme, composed in 1899, carries the name Enigma, a title that the composer did nothing to discourage, but which also has given rise to much speculation. Elgar alluded to a “larger theme…[that] is not played.” He further wrote:

In this music, I have sketched, for their amusement and mine, the idiosyncrasies of fourteen of my friends, not necessarily musicians; but this is a personal matter and needs not have been mentioned publicly. The Variations should stand simply as a “piece” of music. The Enigma I will not explain—its “dark saying” must be left unguessed.

A few years ago, an English musician claims to have solved the “Enigma” by pointing out an unmistakable kinship between Elgar’s theme and a brief motive in the Andante of Mozart’s Symphony no. 38 (“Prague”), a work that shared the program with Elgar’s piece at its premiere. While there has been no scholarly confirmation of this theory, the purely musical evidence is convincing. Arne’s “Rule Britannia” and Bach’s “Art of Fugue” have also been suggested as candidates. Elgar would be amused, no doubt, by the degree of speculation his mystery has sparked.

Ever discreet, Elgar identified the personality behind each variation in the score with only a set of initials, nicknames, or symbols. Sir Ivor Atkins revealed the identities of these friends in an article in the Musical Times after the composer’s death:

- (C.A.E.), L’istesso tempo. Lady Caroline Alice Elgar, the composer’s wife.

- (H.D. S-P.), Allegro. Hew David Stuart-Powell, a pianist.

- (R.B.T.), Allegretto. Richard Baxter Townshend, an amateur actor with the ability to shift his voice from deep basso to falsetto.

- (W.M.B.), Allegro di molto. William Meath Baker, a country squire.

- (R.P.A.), Moderato. Richard Penrose Arnold, son of Matthew Arnold, a daydreamer with a livelier side to his personality.

- (Ysobel), Andantino. Isobel Fitton, a violist student of Elgar.

- (Troyte), Presto. Arthur Troyte Griffith.

- VIII. (W.N.), Allegretto. Winifred Norbury, another pianist.

- (Nimrod), Adagio. Arthur Jaeger, a dear friend who waxed eloquent when discussing the grandeur of Beethoven’s slow movements. This magnificent variation often is used as a memorial tribute.

- (Dorabella), Allegretto. Dora Penny (Mrs. Richard Powell), a friend with a charming stutter. Elgar labels this variation “intermezzo.”

- (G.R.S.), Allegro di molto. George Robertson Sinclair, an organist at Hereford Cathedral, whose pet bulldog, Dan, takes a splash while chasing a stick in the water.

- (B.G.N.), Andante. Basil Nevinson, a cellist who played chamber music with Elgar.

- XIII. (***), Moderato. Lady Mary Lygon, who was on board a ship bound for Australia when Elgar composed the Enigma Variations. The composer quotes (literally in the score) Mendelssohn’s overture, Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage. The three asterisks, as well as the title “romanza” indicate that Elgar harbored special feelings for Lady Mary.

- XIV. (E.D.U.), Allegro. Elgar’s wife (whose variation is evoked within) affectionately called her husband “Edoo.” This triumphant finale is a self-portrait of the composer.

Enigma Variations, which was first performed on 19 June 1899 under the direction of the great German conductor, Hans Richter, stands, along with Brahms’s “Haydn” Variations and Strauss’s Don Quixote as one of the finest examples of free-standing orchestral variations. Accepting Richter’s advice, Elgar made a few modifications in the piece, most notably the addition of the presto coda in the finale.

Program Note by David B. Levy © 2010/2017