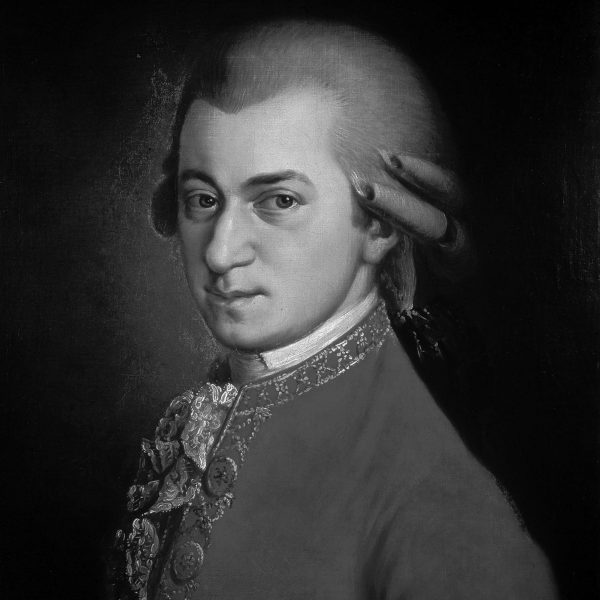

W.A. Mozart:

Symphony No. 35 in D Major, K. 385 “Haffner”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was born January 27, 1756 in Salzburg. He died on December 5, 1791 in Vienna. His Symphony in D Major, K. 385 [no. 35] dates from 1782, i.e., shortly after Mozart took up residence in Vienna. The “K” number used for Mozart’s works refers to the name Ludwig Ritter von Köchel, who first issued the Chronological-Thematic Catalogue of the Complete Works of Wolfgang Amadé Mozart in 1862. The Köchel catalogue has been updated and revised many times to keep pace with musicological revelations. The work is scored for flute, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings.

On July 22, 1776 the Archbishop-principality of Salzburg celebrated the wedding of Sigmund Haffner’s daughter, Elisabeth, to fellow townsman F. X. Anton Späth. The evening before the occasion was marked by a party for which Salzburg’s brightest star, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, willingly provided a festive piece of music (“Haffner” Serenade, K. 248b). Six years later Herr Haffner was elected to be elevated to the nobility. Wolfgang had moved permanently to Vienna by this date, and it fell to his father, Leopold, to write to his son a letter requesting that he compose a new symphony for the Haffner family. This time, however, Wolfgang was not so eager to comply. His new comic opera, The Abduction from the Seraglio, had just been successfully staged in Vienna, which meant—if Mozart hoped to reap any profit from it—he needed to seize the moment. As he wrote to his father on July 20:

Well, I am up to my eyes in work. By Sunday week I have to arrange my opera for wind instruments, otherwise someone will beat me to it and secure the profits instead of me. And now you ask me to write a new symphony too! How on earth am I to do so?

(Quoted from Neal Zaslaw, Mozart’s Symphonies: Context, Performance Practice, Reception, Oxford UP, 1989)

The matter was further complicated by Wolfgang’s impending marriage to Constanze Weber—a union to which Leopold only grudgingly consented. Could this also have been a reason for Wolfgang’s procrastination? One week later he writes:

You will be surprised and disappointed to find that this [mailing] contains only the first Allegro; but it has been quite impossible to do more for you, for I have had to compose in a great hurry a serenade [probably K. 375], but for wind instruments only (otherwise I could have used it for you too). On Wednesday the 31st I shall send the two minuets, the Andante and the last movement. If I can manage to do so, I shall send a march too.

The resulting work was a second “Haffner Seranade,” four movements of which were extracted to create the “Haffner Symphony.” While Mozart was clearly incapable of writing “bad” music, it is just as clear that he lavished little attention on the work’s middle movements, the Andante and Minuet. The outer movements, however, represent Mozart at his finest. The proximity of the “Haffner” Symphony to the “Abduction from the Seraglio” is evident from the principal theme of the symphony’s finale, which is taken almost literally from the aria, “Ha! wie will ich triumphieren!,” sung by Osmin, the sentinel of Pasha Selim’s harem.

One interesting detail about the work’s orchestration: Mozart constantly lamented about the lack of clarinets and clarinetists in Salzburg. The original orchestration for the “Haffner” Symphony calls for no clarinets. When Mozart decided to perform the work in Vienna, however, he added clarinet parts to the first and last movements.

Program Note by David B. Levy, © 2002/2019

Jennifer Higdon:

Low Brass Concerto

Jennifer Higdon was born in Brooklyn, NY on December 31, 1962. She is one of America’s most acclaimed and most frequently performed living composers. She has become a major figure in contemporary Classical music, receiving the 2010 Pulitzer Prize in Music for her Violin Concerto, a 2010 Grammy for her Percussion Concerto and a 2018 Grammy for her Viola Concerto. Higdon enjoys several hundred performances a year of her works, and blue cathedral is one of today’s most performed contemporary orchestral works, with more than 500 performances worldwide. Her works have been recorded on more than sixty CDs. Higdon’s first opera, Cold Mountain, won the prestigious International Opera Award for Best World Premiere and the opera recording was nominated for two Grammy awards. Dr. Higdon now holds the Rock Chair in Composition at The Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. Her music is published exclusively by Lawdon Press. Her Low Brass Concerto was commissioned by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and co-commissioned by the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra and the Philadelphia Orchestra. It was composed in 2017 and was first performed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Riccardo Muti on February 1, 2018. The low brass soloists consist of two tenor trombones, bass trombone, and tuba. The orchestration calls for 2 flutes, 2 oboes, clarinet, bass clarinet, bassoon, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, timpani, percussion, and strings.

Jennifer Higdon, whose Machine was performed by the Winston-Salem Symphony during its 2018-19 season, is one of America’s leading composers. Her works are frequently performed to the acclaim of critics and audiences alike. Her Low Brass Concerto, which features three trombones and tuba, is a true example of an ensemble group of soloists, as opposed to a work that gives free reign for each of the four soloists to shine on its own. In this sense it takes its place as a modern take on the Baroque ripieno concerto grosso, such as found in Johann Sebastian Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos nos. 3 and 6.

John von Rhein, writing for the Chicago Tribune wrote, “The new work harnesses the signature strength of [the CSO’s low brass section] in imaginative ways that allow them to function as a unit, duo, trio and individual voices, before her 17-minute, single-movement concerto charges to a rousing close.” He went on to write that the work “is a big-shouldered Chicago brass blowout if there ever was one — beautiful, accessible, inventive, impeccably crafted — drawing not so much on its muscular might as on its ability, less often recognized, to play softly and lyrically.”

Program Note by David B. Levy, © 2019

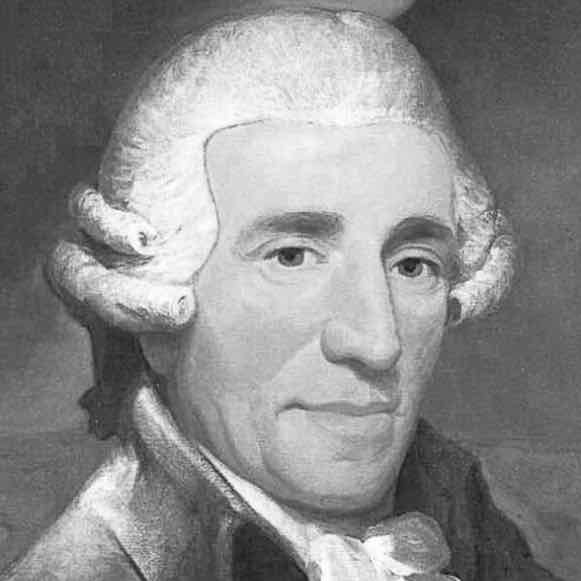

F.J. Haydn:

“The Representation of Chaos” from The Creation

Joseph Haydn was born in Rohrau, Lower Austria on March 31, 1732 and died in Vienna on May 31, 1809. His long and productive career spanned the end of the Baroque Era to the onset of the Romantic. Famed for his incomparable contribution to the development of the symphony and string quartet, Haydn composed an enormous amount of music in other genres, including sacred choral music. His last two oratorios, The Creation and The Seasons were inspired by the magnificent examples of Handel. The first public performance of The Creation took place in Vienna’s Burgtheater on March 19, 1799. It is scored for four vocal soloists, chorus 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, and strings.

If ever a musical work could be designated the capstone of a composer’s career, surely Haydn’s oratorio the Creation fills this role. Haydn took more than fame, fortune, and fond memories when he made his final departure from England in August of 1795. He carried in hand a gift from his friend and patron, Johann Peter Salomon, in the form of a libretto (unfortunately now lost) based in part on John Milton’s Paradise Lost entitled The Creation of the World. This text ostensibly was to have been set to music by George Frideric Handel, the performance of whose oratorios Haydn attended with great pleasure during his sojourns in London. Upon his return to Vienna, another Handel enthusiast, the Baron Gottfried Freiherr van Swieten could barely suppress his enthusiasm: “I recognized at once that such an exalted subject would give Haydn the opportunity I had long desired, to show the whole compass of his profound accomplishments and to express the full power of his inexhaustible genius.”

Such was now the state of affairs for Haydn, now well into his sixty-fourth year. Still full of energy and fertile of imagination, new music from his pen was very much in demand everywhere. No longer interested in the composition of symphonies (he had, after all, composed 106 of these), Haydn turned his attention more and more to choral music. His last six settings of the Mass, a wonderful setting of the Te Deum, and two oratorios—The Creation and The Seasons—represent the mature fruit of a wonderfully creative life. Work on The Creation began in the latter months of 1796 and lasted until March 1798. After private performance on April 30 at the Schwarzenberg Palace in Vienna, the first public performance took place at Vienna’s Burgtheater with approximately 180 participants on March 19, 1799. By December of that year, a tradition began of performing The Creation in support of charitable causes. “I know that God has favored me,” Haydn confided with characteristic modesty, “but the world may as well know that I have been no useless member of society, and that one can also do good by means of music.” A wonderful expression of the affection and respect with which Haydn was held by his peers was a seventy-sixth-birthday gala performance of The Creation under the direction of Antonio Salieri at the Great Hall of the University of Vienna on March 27, 1808. The audience on this occasion not only included a “who’s who” of Vienna—including Haydn’s former pupils Beethoven and Hummel—but also the city’s aristocracy. The honoree, however, was so frail that he had to be carried into the auditorium and was unable to remain for the entire concert. Even the proud Beethoven, who only a few years earlier claimed in an uncharitable moment to have learned nothing from Haydn, shed his arrogance and kissed his old teacher on the hands and forehead.

The Creation is a work marked by an astonishing number of “firsts.” It is, as best we know, the first original vocal composition to be simultaneously conceived in two languages—English and German (translation by van Swieten, who also made musical suggestions). Nowhere is Haydn’s continued innovative spirit more evident than in the extraordinarily poignant instrumental introduction to The Creation, “The Depiction of Chaos.” Here is no Handelian overture. Haydn gives us instead mysterious introduction filled with disorder, harmonic surprise, and unexpected outbursts of fierce dissonance. All these characteristics demonstrate a “romantic” pictorialism that stretches the musical vocabulary of the late eighteenth century.

Program Note by David B. Levy, © 2010/2019

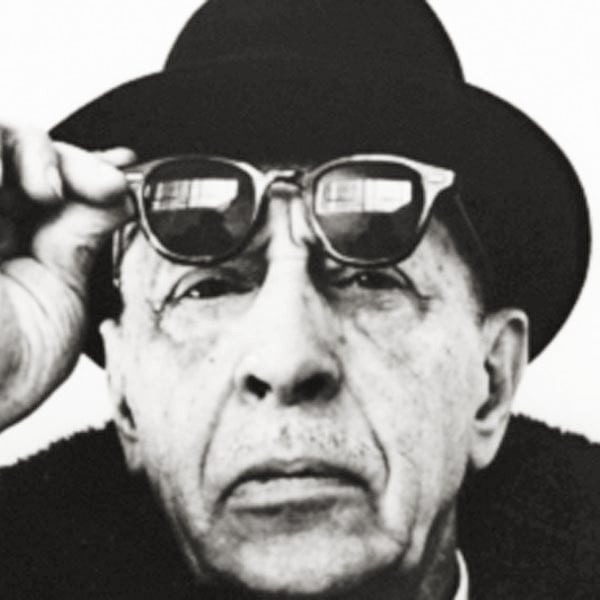

Igor Stravinsky:

The Rite of Spring

One of the towering figures of twentieth-century music, Igor Stravinsky was born in Oranienbaum, Russia on June 17, 1882 and died in New York City on April 6, 1971. His best known works remain the three ballet scores based on Russian themes and scenarios—The Firebird (1910, rev. 1919, 1945), Petrushka (1910-11, rev. 1947), and The Rite of Spring (1913, rev. 1921). All three scores were composed for fellow ex-patriot Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, based in Paris. Stravinsky wrote works that encompass many genres and explore a wide variety of musical styles, all of which bear his own distinctive traits. The Rite of Spring was the result of a collaboration among the composer Stravinksy, the choreographer/dancer Vaslav Nijinksy, and the ethnologist/scenic and costume designer, Nicholas Roerich. Hovering above the three was the impresario and director of the Paris-based Ballets Russes, Sergei Diaghilev. The ballet received its first performance on May 29, 1913 at Paris’s Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. Pierre Monteux conducted and created a scandalous sensation because of its unorthodox choreography and music. It was performed as a concert piece for the first time on February 18, 1914 in St. Petersburg conducted by Serge Koussevitzky. The huge score calls for piccolo, 3 flutes (3rd doubling second piccolo), alto flute, 4 oboes (4th doubling second English horn), English horn, 3 clarinets (3rd doubling second bass clarinet), soprano clarinet, bass clarinet, 4 bassoons (4th doubling second contrabassoon), contrabassoon, 8 horns (7th and 8th doubling Wagner tubas), 5 trumpets (including a trumpet in D and bass trumpet), 3 trombones, 2 tubas, timpani, large percussion section, piano, harp, and strings.

“He who hesitates is lost,” goes the old saying. The composer Anatol Liadov, who was supposed to have composed the music for a new ballet based on the legend of the Firebird that Sergei Diaghilev planned to produce in his second Paris season, ought to have paid attention to the adage’s warning. Fortunately for the young Igor Stravinsky, Liadov did not, and the great opportunity for which Stravinsky had been hoping was now at hand. Diaghilev already had been sufficiently impressed with the talent of the precocious student of Rimsky-Korsakov to commission orchestrations of two piano pieces by Chopin from him in 1909. But a chance to collaborate as a full partner with the likes of choreographer-dancer Mikhail Fokine was almost too good to be true. The success of Stravinsky’s score to The Firebird, first performed at the Paris Opéra on June 25, 1910 under the baton of Gabriel Pierné, was legendary. This ballet remains to this day the most popular of all Stravinsky’s scores. Over the next two years (1911 and 1913) Stravinsky was to follow the success of The Firebird with Petruchka and the epic Rite of Spring (Le sacre du printemps).

Of these three ballet scores, none was to have the impact of the Rite of Spring. Translated more literally from the Russian, its title might better be called “Sacred Spring.” Because its premiere took place in Paris under a French title, it is also called Le sacre du printemps. Popularwisdom would have it, fed in part by Stravinsky and Diaghilev’s genius at self-promotion, thatthe work’s exotically orchestrated and rhythmically dynamic score, taken on its own, incited a riot at its premiere. It was in fact primarily the choreography that provoked the audience. Nevertheless, all of the elements that make up the Rite of Spring was aimed toward its ability to shock. The work’s subtitle, “Portraits of Pagan Russia,” and its loosely-woven plot create together a vivid and exotic theatrical work whose elemental qualities, especially its focus on rhythmic energy, continue to thrill audiences. The harmonic and melodic elements are derived from rhythmically-altered versions of over thirty melodic fragments derived largely from Lithuanian folksongs, and whose character is informed by pitch material is infused with octatonic, whole tone, and pentatonic scales.

The ballet itself comprises two large sections. Part I, “Adoration of the Earth,” includes seven discrete sections that are, in Robert Winter’s useful image, “spliced” together like scenes from a movie. The “Introduction” begins with a wailing solo bassoon played at the top of the instrument’s range, and whose effect is that of a mystical incantation. It is followed by a colorful passage in the woodwinds that imitate, in Stravinsky’s words, “a swarm of spring pipes.” The curtain opens on a powerful “Augers of Spring/Dance of the Adolescents,” depicting a kind of mating ritual. The “primitive” feeling of this music is produced by an insistent four-note ostinato (repeating) figure whose simplicity is complicated by heavy accents in unexpected places. This scene leads to a fast-paced “Ritual of Abduction” that ends suddenly with trills in the flutes. “Spring Rounds” ensues as the young girls of the tribe dance in solemn procession. This passage builds to a fever pitch that finally unleashes its energy. An exciting “Ritual of Rival Tribes” is interrupted by the “Procession of the Sage,” whose arrival leads to his blessing of the newly-awakened earth after the long, cold, Russian winter. The sanctification process leads to ecstatic rejoicing in the “Dance of the Earth” that concludes Part I in abrupt fashion.

Part II, “The Sacrifice,” comprises five scenes, beginning with the “Mystic Circles of the Young Adolescent Girls,” from whom a sacrificial virgin is to be chosen. Eleven powerful loud strokes indicate that one has been selected and leads to the “Glorification of the Chosen One,” the rightness of which in turn is confirmed in the “Evocation of the Ancestors.” The girl is turned over to the elders of the tribe in the hypnotic “Ritual Action of the Ancestors.” The work concludes with the “Sacrificial Dance” in which the chosen virgin dances herself to death in one of the rhythmically and metrically complex passages of the entire score. Stravinsky continued to revise the score after 1920 after finding errors in the first edition, and in some cases rewriting and re-notating many passages. This editorial process continued even after the composer’s death. Butnone of this has changed the Rite of Spring’s place as one of the seminal works of the twentieth century and its capacity to excite audiences throughout the world.

Notes by David B. Levy © 2019