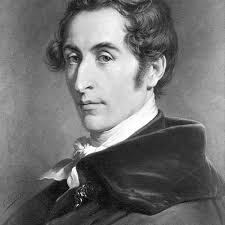

Carl Maria von Weber

Overture to Der Freischütz

Carl Maria von Weber was born in Eutin (Germany), presumably on November 18, 1786, and died in London on June 5, 1826. Best known today for his ground-breaking Romantic opera, Der Freischütz (1821), he also wrote other operas, significant choral music, and instrumental works. His overtures were especially influential in the development of the concert overture and symphonic poem. Although opus numbers exist for some of Weber’s compositions, scholars use “J” numbers that refer to the 1871 chronological thematic catalogue of his works prepared by Friedrich Wilhelm Jähns. This catalogue may be compared to the catalogue of Mozart’s compositions by Ludwig von Köchel (the source of “K” numbers for that composer). Weber’s Overture to Der Freischütz is scored for 2 piccolos, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, percussion, and strings.

Weber’s 1821 opera, Der Freischütz, quickly became the standard that defined German Romantic Opera. Supernatural events, a rural landscape (the forest), religiosity, an alienated hero, and, above all, redemptive love are its primary ingredients. It is safe to say that without Weber’s model, the operatic achievements of Richard Wagner later in the nineteenth century would have been unthinkable. Beloved by the German people—but not to the exclusion of other nationalities—Der Freischütz is a work whose plot (based on Germanic folklore) and musical attributes were admired by not only Wagner, but also by the Frenchman Berlioz and many others.

The title of the opera defies precise translation, having been called at times The Free Shooter or The Magic Bullet. The libretto by Friedrich Kind tells the story of the unlucky Max, a hunter whose skill as a marksman has abandoned him at a critical moment. If he is to win the hand of his beloved Agathe, he must succeed in the shooting contest at the local hunting lodge. He turns in desperation to black magic, abetted by his companion, Caspar. This brooding friend had at some time before the story begins sold his soul to Samiel, a werewolf agent of Satan, also known as the “Black Hunter.” Envious of Max, Caspar hopes to offer his companion’s soul to Samiel as a substitute for his own. Against all better judgment, Max agrees to meet Caspar at midnight in the dreaded Wolf’s Glen, where seven magic bullets will be cast that cannot fail to hit their mark.

The gloomy music for the finale of Act II, the “Wolf’s Glen scene,” provides much of the material heard in the Overture to Der Freischütz. After an opening gesture in the unison strings, a hymnal melody for four horns (the German name for this instrument, appropriately enough, is Waldhorn [Forest horn]) dominates the slow introduction. The serenity is interrupted by a ominous chord, played by tremolo strings and punctuated by the kettledrum. This chord is heard throughout the opera whenever Samiel is present. An agitated theme with syncopated accompaniment provides the first theme for the Overture’s main section, which is cast in sonata form. This dark melody is derived from Max’s aria in Act I, “Doch mich umgarnen finstre Mächte” (“Thus sinister powers ensnare me”). An explosive loud theme represents the thunderstorm that erupts at the climax of the “Wolf’s Glen scene,” at the casting of the fatal seventh bullet, which belongs to Samiel and will hit the target of his choosing. Another theme, played by the clarinet (one of Weber’s favorite instruments), is also taken from the “Wolf’s Glen scene.” A lyrical second theme played by the violins is derived from Agathe’s aria, “All’ meine Pulse schlagen” (“All my pulses are beating”). The triumph of Agathe’s redemptive love is reflected in the coda of the Overture, where a dramatic pause is followed by a joyful reprise of her melody. Listener’s familiar with the Overture to The Flying Dutchman will recognize just how indebted Wagner was to Weber’s superb model.

Program Note by David B. Levy © 1992/2018

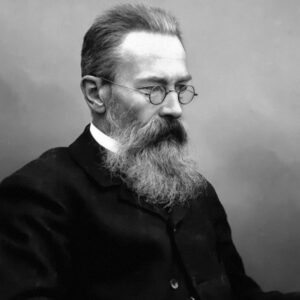

Dmitri Shostakovich

Concerto No. 1 in E-flat Major for Violoncello and Orchestra, Op. 107

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, one of the Soviet Union’s greatest composers, was born in Saint Petersburg on September 12, 1906 and died in Moscow on August 9, 1975. Although he composed in a wide variety of genres, he is best known for his fifteen symphonies, works that stand among the finest examples of the genre from the mid-twentieth century. His Concerto no. 1 for Violoncello and Orchestra, op. 107, was composed in 1959 for the Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich. It was first performed on October 4, 1959, with Yvgeny Mravinsky conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra in the Large Hall of the Leningrad Conservatory. It is scored for solo cello, 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 1 French horn, timpani, celesta, and strings.

Arguably the greatest composer of symphonies and concertos in the twentieth century, Shostakovich’s life was fraught with anxiety as his career spanned the outbreak of the 1917 Russian revolution, the tyranny of Joseph Stalin, and beyond. As a free-thinker and creative artist, his music was frequently subjected to criticism from Soviet officialdom, especially when the powers-that-be felt he strayed from the path of “socialist realism.” Born with a nervous disposition, the pressure under which he had to work certainly exacerbated his neuroses, which sometimes rise to the surface in his music.

His Concerto no. 1 for Cello and Orchestra (his Concerto no. 2, a far darker and introspective piece, was composed for Rostropovich in 1966), has emerged as one of his masterworks, and represents his post-Stalin reconnection with the West which included successful tours of the United States. Indeed, this piece is a representative example as one of its first recordings was with Rostropovich and the Philadelphia Orchestra under the direction of Eugene Ormandy, made under the composer’s supervision. It is interesting to note that Rostropovich eventually defected to the U.S. and became the music director of the National Symphony in Washington, D.C. The piece was inspired in part by the Sinfonia Concertante for Cello (1952) by fellow Soviet composer, Sergei Prokofiev—a work that Shostakovich very much admired.

The piece is conceived in four movements, the last three of which are played without any break. The opening Allegretto begins straight away with the solo cello robustly sounding the four notes that are derived from the letters found in composer’s name (D-S-C-H = D-E-flat-C-B-natural), albeit transposed both in order and specific pitch names. A prominent feature of the work is the writing for the solitary French horn, who acts as a kind of subordinate solo instrument. This feature is also prominent in the concerti for wind instruments by the Danish composer, Carl Nielsen. Indeed, Shostakovich’s Piano Concerto no. 1 features solo trumpet.

The second movement is a haunting Moderato. Toward the movement’s end, the soloist plays the theme in harmonics, with eerie responses from the celesta. This goes immediately into an extended written-out cadenza (third movement) that grows more and more agitated as it unfolds, leading directly into the finale, an Allegro con moto, a movement that speaks with heavy Russian accents.

Program Note by David B. Levy, © 2018

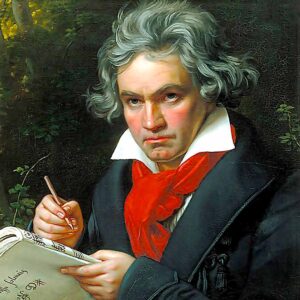

Johannes Brahms

Symphony No. 3 in F Major, Op. 84

Johannes Brahms was born on May 7, 1833 in Hamburg and died in Vienna on April 3, 1897. One of the dominant composers of the late nineteenth century, Brahms greatly enriched the repertory for piano, organ, chamber music, chorus, and orchestra. His Symphony no. 3 was composed in 1883 and was first performed in Vienna on December 2 of that year with the Vienna Philharmonic under the direction of Hans Richter. The work is scored for 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabasson, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, and strings.

The Third Symphony of Brahms is at once the shortest, simplest and the most complex of the four symphonies he composed between 1876 and 1884. The year of the composition of the Third Symphony, 1883, marked thirty years since the publication of the article, “New Paths,” that appeared in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, written by his mentor, Robert Schumann, and that touted the then twenty-year-old Brahms as the legitimate heir to Beethoven’s muse. The year was also marked by the death, on February 13, of Richard Wagner—a figure who believed that only he himself was entitled to that lofty claim. Brahms’s indebtedness to Schumann is clearly evident in the Third Symphony, which echoes Schumann’s own Symphony no. 3. Common wisdom dictated that Brahms and Wagner were representatives of two mutually exclusive artistic positions, but from musical grounds, there are compelling reasons to call this view into question.

Both Brahms and Wagner were symphonic composers grounded solidly in the nine symphonies of Beethoven. The principal difference lay in their artistic goals, but not always in the means used to attain them. Wagner focused almost exclusively on opera, while Brahms continued to compose symphonies, sonatas, chamber music, Lieder, choral music, and in other traditional instrumental genera. What might be called a Wagnerian feature found in Brahms’s Third Symphony is the application of leitmotif-style techniques that serve to unify its four movements, often in a most dramatic fashion. The most important of these motives is presented in the first three measures of the work (F, A-flat, to the F an octave higher). The influence of this motto pervades the entire piece, sometimes in hidden or transformed ways, a favorite device of Wagner. Schumann also was not averse to using musical codes of this type.

But if we permit Brahms to remain the bastion of abstract musical logic devoid of poetic text, this motto is a significant gesture for its melodic and harmonic implications—especially in the symphony’s finale. Another case is the serene second theme from the second movement. The return of the descending arpeggio theme in the finale’s coda, a musical gesture first heard in the earliest moments of the first movement serves to confirm the symphony’s cyclic nature. Another example of the work’s interconnectedness is the appearance of mysterious chords in the second movement that reappear unexpectedly and with great dramatic impact in the development section of the finale.

The true beauty of the Third Symphony is that its complexity is couched in the surroundings of the simplest and most appealing melodiousness. Brahms possessed the gift of creating tension through modal and metrical ambiguity—techniques that he learned from the study of music of Schubert and Schumann. The rhythmic complexities of this symphony are extraordinary, even for Brahms, and the conflict of the major and minor modes remain unresolved until near the end of the work.

Program Note by David B. Levy, © 1995/2018