Sergei Rachmaninoff:

Symphony No. 2 in E minor, Op. 27

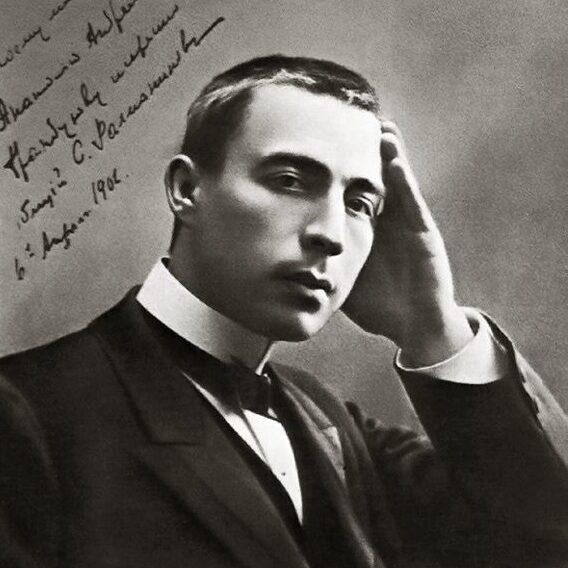

The great Russian pianist, conductor, and composer, Serge Rachmaninoff was born in Oneg on March 20 /April 1, 1873, and died in Beverly Hills, CA, March 28, 1943. He was, in many ways, the last great representative of Russian Romantic style brought to fruition by Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov and other Russian composers. This in no way prevented Rachmaninoff from developing a thoroughly personal idiom, whose lyricism is enhanced by a sure grasp of form and brilliance of orchestration. His Symphony no. 2 was first performed on January 26, 1908 at St. Petersburg’s Mariinsky Theater with the composer himself conducting. The work is scored for 3 flutes (piccolo), 3 oboes, 2 clarinets (bass clarinet), 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, glockenspiel, bass drum, cymbals, and strings.

Rachmaninoff, one of the great pianists and composers of the late-Romantic Russian tradition, had a disastrous first experience as a symphonist. His Symphony no. 1, composed in 1895, received its first performance on March 27, 1897, with Alexander Glazunov conducting, and the event was an unmitigated failure. According to Rachmaninoff’s wife, Glazunov was drunk, although it may have been that he simply did not care for the piece. Cesar Cui called it “a program symphony on the Seven [?] Plagues of Egypt,” a work that relied on “the meaningless repetition of the same short tricks.” Other critics more charitably acknowledged that the piece was badly performed.

Terrence Wilson performs Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 1 on a program that includes music Seeger and Rachmaninoff, January 7 & 8, 2023.

Rachmaninoff went into a deep depression that lasted for three years, and it seemed for a time that the world would be deprived of any further compositions from his pen. Fortunately, with the help of a physician, Dr. Dahl, and through continued work as a performer, Rachmaninoff worked though the trauma, emerging in 1900-1901 with his popular Second Piano Concerto. Beset by pressures at home, the composer took up residence in Dresden, Germany in 1906. The composition of his Symphony No. 2 in 1906-1907 in the seclusion of Dresden was a sure sign that his confidence as a composer of symphonies had been completely rehabilitated (his Third Symphony, however, was not composed until 1935-1936). It was indeed fortunate that by 1908, Rachmaninoff was in a position to direct the premiere of the piece himself. This he did on January 26 at St. Petersburg’s Mariinsky Theater. A performance at the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow took place on February 2.

Rachmaninoff’s Second Symphony is cast in four movements. The first movement, Largo – Allegro moderato, begins solemnly in the lower strings, out of whose depths a lyrical, turning theme emerges in the violins. A brief phrase in the English horn leads to the main body of the movement, whose opening theme bears resemblance to that of the introduction, and whose modal inflections reveal the composer’s Russian roots. A lushness of string sonority and a wealth of tunefulness dominate the remainder of the movement, which, despite its outpouring of passion, never quite escapes the spirit of its melancholic opening. The second movement, Allegro molto, is a scherzo in duple meter. The opening is particularly arresting, as four unison horns pronounce its principal theme. A lyrical second theme comes next, followed by a truncated statement of the opening theme. A crash of cymbal and flurry of violins announce the dramatic trio section, the end of which leads back to a reprise of the opening, now with added touches of orchestration. The movement ends softly, as if the orchestra had expended its last ounce of energy.

The emotional heart of the symphony is its Adagio third movement. Its principal tunes are sung by the clarinet and the violins, and themes from the previous movements—above all the turning melody of the first movement—are brought back for brief appearances. The finale, Allegro vivace, opens boldly with a tarantella-like tumult. This soon yields to a serious-minded march and a passing reference to the beginning of the scherzo. The dance interrupts this, but it too must yield to Rachmaninoff’s intrinsic lyricism, and a romantic new tune appears in the violins. Additional references to the first three movements are heard. Ultimately, however, the soaring lyrical themes and energetic tarantella triumph as the symphony ends in a burst of glory.

Program Note by David B. Levy, © 2022