John Hammarback Oboe

Winston-Salem Symphony

Edwin Outwater Conductor

October 2015

John Hammarback Oboe

Winston-Salem Symphony

Edwin Outwater Conductor

October 2015

Estonian composer, Arvo Pärt was born in Paide, the capital of Estonia’s Järva County, on September 11, 1935. Known for the quiet spirituality of his music, Pärt turned away from his earlier modernistic style, to develop a mode of composition in the 1970s called “tintinnabuli.” The root of this style evokes the ringing of bells. First applied in his works, Für Alina (1976), Fratres (1977) and Spiegel im Spiegel (1978), the technique also is used in the Cantus in Memoriam Benjamin Britten. Composed in 1977, a few months after Britten’s death in 1976, Pärt’s Cantus was first performed on April 7, 1977 in Tallinn, Estonia by the Estonian National Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Eri Klas. The effect of the piece evokes a kind of neo-medievalism inspired by the composer’s deep religiosity. His music has resonated with audiences throughout the world to such an extent that his music is performed more frequently than any modern composer except for John Williams. Cantus is scored for one tubular bell and string orchestra.

The idea of a composer memorializing or honoring a fellow artist is a tradition that goes back at least to the Renaissance Era. One particularly beautiful example is Josquin Desprez’s Déploration sur la mort de Ockeghem (“Nymphes des bois”), composed as a lament on the death of the Franco-Flemish composer, Jehan Ockeghem (d. 1497). Ockeghem was not only a fine composer, but was also the teacher of the next important generation of composers that included Josquin himself. This motet, written to a French text, comprises two sections, the first of which is in the style of Ockeghem, while the second part, Josquin writes in his own compositional voice. Embedded within one of the voices of the music is the words and music of the medieval Latin plainchant, “Requiescat in pace” (“Rest in Peace”).

If finding one’s own true voice while simultaneously honoring the past is the goal of an artist, Arvo Pärt certainly has been successful. In his Cantus in Memoriam Benjamin Britten, Pärt uses compositional devices that reach back to the Medieval-Renaissance laments. A double-edged device he employs is a repeating slowly descending natural scale (Aeolian mode), a gesture associated often with laments. The music is framed by silence, after which the tubular bell, pitched in “A,” represents the tolling of a church bell. Pärt then calls for the divided violins to play the descending scale, with the lower parts playing only notes that comprise the natural scale. The violas play it slower, while the lower voices play it at an even slower pace. This technique, known as “prolation,” was used by composers such as Ockeghem and Josquin, as well as later composers. The music begins softly, growing gradually in volume and density.

Speaking of the Cantus, Pärt remarked, “Why did the date of Benjamin Britten’s death—4 December 1976—touch such a chord in me? During this time I was obviously at the point where I could recognize the magnitude of such a loss. Inexplicable feelings of guilt, more than that even, arose in me. I had just discovered Britten for myself. Just before his death I began to appreciate the unusual purity of his music … And besides, for a long time I had wanted to meet Britten personally—and now it would not come to that.”

Program Note by David B. Levy, © 2024

Benjamin Britten, one of England’s leading twentieth-century musicians, was born in Lowestoft, Suffolk on November 22, 1913 and died in Aldeburgh on December 4, 1976. Britten’s contribution to opera (Peter Grimes, The Turn of the Screw, Billy Budd), sacred and secular choral music (A Ceremony of Carols, War Requiem), and vocal and instrumental repertory is impressive, both in quantity and quality, and is widely admired for its superb craftsmanship and expressive power. His Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings, composed in 1943 at the request of the virtuoso hornist, Dennis Brain, is a cycle of six settings of nocturnal British poems dating from the 15th through the 19th centuries, flanked by a Prologue and Epilogue for solo horn. Britten was aided in the choice of poems by the music critic and novelist, Edward Sackville-West, to whom the work is dedicated. The first performance of Britten’s Serenade took place on October 15, 1943 at London’s Wigmore Hall. Tenor Peter Pears and Brain were joined by conductor Walter Goehr and his orchestra.

The years that have elapsed since Benjamin Britten’s death in 1976 have only served to enhance the reputation that accrued to him during his lifetime—not only one of the greatest composers in the history of English music, but also one of the twentieth century’s most important musical figures. Furthermore, Britten was arguably the finest setter of English words into music since the seventeenth-century master, Henry Purcell. The composer’s Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings joined together the skills of the legendary hornist, Dennis Brain and lyric tenor, Peter Pears in service of six poems that address the subject of night in its various aspects. Indeed, the word serenade derives from the Italian name for music that was performed in the evening—either for parties or to woo a lover. Mozart’s Eine Kleine Nachtmusik and Sondheim’s musical, A Little Night Music, are German and English diminutive versions of a serenade. As was often the case, Britten’s writing for the tenor voice was guided by the special qualities of Pears’ voice, a singer who was also the composer’s life-companion and collaborator.

The Prologue and Epilogue for solo horn were composed with the acoustical properties of the natural horn (i.e., an instrument with no valves). As a result, some of the pitches may sound “out of tune” to the astute listener. It is therefore important to bear in mind that these strange pitches are not mistakes but represent the composer’s desire. The work then presents the settings of six poems:

Program Note by David B. Levy, © 2024

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was born January 27, 1756 in Salzburg. He died on December 5, 1791 in Vienna. The Symphony no. 41, K. 551, composed in 1788, was the composer’s last effort in the genre. The date of its first performance is unknown. The “K” number used for Mozart’s works refers to the name Ludwig Ritter von Köchel, who first issued the Chronological-Thematic Catalogue of the Complete Works of Wolfgang Amadé Mozart in 1862. The Köchel catalogue has been updated and revised several times. The “Jupiter” Symphony, whose popular title was not given by the composer, is scored for flute, 2 oboes, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings.

Mozart’s last three symphonies were composed over a period of six weeks during the summer of 1788—an almost unbelievable feat, even for a composer who was famed for working at a breakneck pace. Together they represent the zenith of the 18th-century symphonic process. Their grandeur suggests that they were composed for public performance in Vienna, as opposed to any private function, and it may be that Mozart intended to use them for a series of concerts for his own benefit. Such concerts, however, never materialized and the great triptych remained unperformed until after the composer’s death. The last of these at some point in the nineteenth century became identified as the “Jupiter,” although programs featuring this work often identified it as the “Symphony with the closing fugue.” The reason for this title is readily apparent upon hearing it.

The “Jupiter” Symphony is uncommonly rich, even for the melodious Mozart, in its abundance of thematic content. The imposing Allegro vivace first movement reveals at once that here is a symphony of great formal design and dignity. The form of the movement itself is not especially anomalous, but Mozart’s deft manipulation of its many-faceted themes – now martial, now operatic, now lyrical (here Mozart is quoting himself—an aria, “Un bacio di mano,” K. 541, composed to be inserted in the opera Le gelosie fortunate by Anfossi), now brilliant – never fails to inspire wonder. Only a composer of great experience and surety could have penned this work. The first movement’s expansiveness hides its remarkable economy of means. A perfect example of this comes at the beginning of the central development section wherein Mozart effects a spectacular modulation from G Major to E-flat Major in the course of only four notes in the woodwinds. The work’s second movement, Andante cantabile, shows a lyricism derived from the world where Mozart stood without peer—Italian opera. Even here the composer has succeeded in outdoing himself in intensity of expression. After a superb Allegretto minuet, we arrive at the finale, Allegro molto that stands as a beacon flashing Mozart’s supreme mastery of form. Despite the appellation given in nineteenth-century programs, this finale is not a formal fugue. It does, however, make considerable use of fugal techniques within the context of classical sonata form. Precedents for extensive fugal writing in finales may be found in Joseph Haydn’s String Quartets, Op. 20, Nos. 2, 5, and 6, as well Mozart’s String Quartet in G Major. In the two examples by Mozart the composer joins, as only he could, the textures of homophony (melody and accompaniment) and imitative counterpoint into a monument never exceeded by his successors. The coda (concluding section) of the finale combines no fewer than five independent themes simultaneously. Mathematically speaking, that presented Mozart with no fewer than one hundred and twenty-five possibilities for contrapuntal manipulation! The beauty of all this lies in the fact that none of this sounds contrived, formal, or “scientific.” But acknowledgement of the achievement makes us stand in even greater awe of Mozart’s pure genius.

Program Note by David B. Levy, © 2006/2016/2024

American fiddle player, composer, guitarist, mandolinist, and educator, Mark O’Connor is one of several musicians, including recent Winston-Salem Symphony guest artists Chris Thile, Edgar Meyer, and Bela Fleck, who have crossed the line between traditional American musical idioms and the world of the Classical concert hall. O’Connor, along with his wife, Maggie, have ignited audiences with their electric stage presence and sheer virtuosity. “Strings and Threads Suite” came to life as part of a 2001 recording project with Scott Yoo called “American Seasons.” According to a website, “Strings & Threads Suite” traces O’Connor’s “version of how folk music on the violin evolved in America through thirteen pieces in progressively more modern styles.” Composed for solo violin and strings, the work comprises thirteen short movements played in succession entitled “Fair Dancer’s Reel,” “Sailor’s Jig,” “Captain’s Jig.” “Off to Sea,” “Pilgrim’s Waltz,” “Road to Appalachia,” “Shine On,” “Cotton Pickin’ Blues,” “Pickin’ Parlor Rag,” “Queen of the Cumberland,” “Texas Dance Hall Blues,” “Swing,” and ending with “Sweet Suzanne.” The work presents the listener with a panorama of musical Americana that is now filled with infectious rhythms and gentle reflection—in short, a wonderful journey of fiddling.

O’Connor’s “Double Violin Concerto” was composed in 1997. It received its premiere in 1999 with Nadja Solerno-Sonnenberg and Mark O’Connor as soloists with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. The entire piece comprises three movements. This concert by the Winston-Salem Symphony will present the second movement, “Midnight on the Dance Room Floor,” and the first movement, “Swing,” in that order.

Program Note by David B. Levy, © 2024

Aaron Copland was born in Brooklyn, NY on November 14, 1900, and died in North Tarrytown, NY on December 2, 1990. In addition to his distinguished accomplishments as a composer, he was an important author on musical topics, as well as a gifted pianist and conductor. Furthermore, he was a mentor to at least two generations of important American composers. Copland, more than any composer in the 20th century, gave classical music a distinctly “American” voice that created a model that inspired future composers of film scores such as Elmer Bernstein’s music for “The Magnificent Seven” that shares this program. Included in this voice is an evocation of the American West, as found in his 1938 ballet for impressario Lincoln Kirstein and choreographer Eugene Loring’s “Billy the Kid,” which received its premiere in a two-piano version with the Ballet Caravan Company at Chicago’s Civic Opera House on October 16, 1938. The orchestral version received its first performance in New York City on May 24, 1939. “Rodeo,” another Western-themed ballet by Copland, was composed for Agnes de Mille in 1942. “Billy the Kid” is scored for piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, large percussion section. harp, and strings.

In the earliest stages of Copland’s compositional career, he was very much the modernist and like many other ex-patriots, he travelled to Paris to take in the exciting cultural milieu of Debussy, Ravel, Stravinsky, and others. He was the first of several Americans to study with the legendary Nadia Boulanger. Copland eventually saw a new possible path forward by tapping into American history and folklore. His three popular ballet scores—Billy the Kid, Rodeo, and Appalachian Spring—each reflect his success in weaving modernist techniques together with folk melodies. Of these scores, Rodeo leans most heavily on borrowed tunes, some of which were suggested by choreographer Agnes de Mille. “Billy the Kid” similarly makes use of cowboy and folk tunes, including “Great Grandad,” “Git Along, Little Dogies,” “The Old Chisholm Trail,” and “Goodbye Old Paint.”

The scenario for the ballet is set in the 1870s and 80s in New Mexico and Arizona. The first movement of the Suite is called “Introduction: The Open Prairie,” which sets the scene, at first gently, then more boldly. The following movement, “Street Scene in a Frontier Town,” places the listener more specifically in the American West, as does the “Mexican Dance and Finale” that ensues. After a gentle “Prairie Night,” an exciting “Gun Battle” follows—a movement that makes effective use of the orchestra’s percussion section. A satirical “Celebration” illustrates the joy of townspeople after Billy’s capture. The Suite ends with “Billy’s Death” at the hand of sheriff Pat Garrett, and a reprise of “The Open Prairie.”

Program Note by David B. Levy, © 2024

American composer, conductor, and arranger, Elmer Bernstein, was born on April 4, 1922 in New York City and died in Ojai, California on August 18, 2004. He was responsible for the creation of over 100 film scores throughout his distinguished career. Among these were several Westerns, such as the score for John Sturges’s 1960 film, “The Magnificent Seven” featuring an all-star cast that included, among others, Yul Brynner, Steve McQueen, James Coburn, Charles Bronson, and Eli Wallach is the villain, Calvera. Based on Akira Kurosawa’s “Seven Samurai,” this classic tells the tale of citizens of a Mexican village buying hired gunmen from across the border to rid them of a gang of thieves.

In the history of movies, it has not been uncommon to find that the musical score has provided the most profound memories. Before John Williams and Hans Zimmer came on the scene, many refugees from Europe, such as Erich Wolfgang Korngold and Max Steiner provided Hollywood with some of the most effective musical backgrounds. The music composed by Elmer Bernstein for the classic Western, “The Magnificent Seven” may be counted among the greatest of all time.

Program Note by David B. Levy, © 2024

Danish composer Carl Nielsen was born in Sortelung, near Nørre Lyndelse, Funen, on June 9, 1865, and died in Copenhagen on October 3, 1931. While having written music in a wide variety of styles and genres, he is best known internationally for his six symphonies. His Symphony no. 3 was composed in 1910-11 and he conducted the first performance of it at the Royal Danish Opera in Copenhagen on February 28, 1912. The work’s subtitle, Sinfonia Espansiva is derived from the tempo indication, “Allegro espansivo.” The “FS 60” refers to the Fog and Schousboe catalogue of Nielsen’s music. The symphony is scored for piccolo, 3 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo), 3 oboes (third doubling English horn), 3 clarinets, 3 bassoons (third doubling contrabassoon), 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, and strings. The second movement calls for wordless soprano and baritone voices, although the composer designated these may be replaced with clarinet and trombone, respectively. These performances mark the Winston-Salem Symphony’s first of this work.

It is not easy to describe the music of Carl Nielsen. One the one hand he represents a final blossoming of the great Romantic tradition, while on the other, he was an idiosyncratic innovator. While he was always treasured by his fellow Danes, his international reputation spread starting in the 1950s, due largely to his six symphonies. Four of these have titles, including No. 3 (“Sinfonia Espansiva”) and No. 4 (“The Inextinguishable”). Although Nielsen’s Third Symphony received performances throughout Europe soon after its premiere in 1912, it was not performed in England until 1962. In the United States, Leonard Bernstein was among the first conductors to take an interest in performing and recording Nielsen’s symphonies. When first performed, Symphony No. 3 did not have a subtitle, and it would be a mistake to read too much into its designation of “Espansiva.”

Nielsen offered his own program notes for a performance of the work in Stockholm in 1931:

The work is the result of many kinds of forces. The first movement was meant as a gust of energy and life-affirmation blown out into the wide world, which we human beings would not only like to get to know in its multiplicity of activities, but also to conquer and make our own. The second movement is the absolute opposite: the purest idyll, and when the human voices are heard at last, it is only to underscore the peaceful mood that one could imagine in Paradise before the Fall of our First Parents, Adam and Eve. The third movement is a thing that cannot really be described, because both evil and good are manifested without any real settling of the issue. By contrast, the Finale is perfectly straightforward: a hymn to work and the healthy activity of everyday life. Not a gushing homage to life, but a certain expansive happiness about being able to participate in the work of life and the day and to see activity and ability manifested on all sides around us.

Program Note by David B. Levy, © 2024

The Czech master Antonín Dvořák was born in Nelahozeves, near Kralupy, on September 8, 1841; and died in Prague, May 1, 1904. His Cello Concerto, universally acknowledged to be the supreme masterpiece of its genre, was composed between November 1894 and February 1895. The composer revised it in June 1895 and it received its premiere in London on March 19, 1896. It is scored for 2 flutes (piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, and strings. The last Winston-Salem Symphony performance of this work took place in October 2014, with Yo-Yo Ma as soloist and Robert Moody conducting.

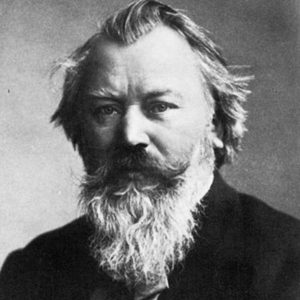

Only the Symphony no. 9 (“From the New World”) surpasses Dvořák’s Cello Concerto in popularity. This magnificent concerto, along with the composer’s Symphony no. 7, represents the Czech master’s work at its finest. It is indeed the cello concerto par excellence, a work that prompted Dvořák’s friend and colleague Johannes Brahms to write in admiration that had he known that such a concerto for this instrument were possible, he “would have written one long ago!” The closest Brahms came to acting on this statement was his composition of a “Double” Concerto for Violin and Cello.

The work stems from the period between November 1894 and February 1895, a time at which Dvořák resided at a brownstone on E. 17th Street in New York City (one block removed from where the author of these notes grew up!). The building, alas, was destroyed a few years ago to make room for an ever-expanding neighborhood medical center. The street, however, was renamed “Dvořák Place.” The famous Czech musician was serving at the time as the Director of the fledgling National Conservatory of Music.

One of the most significant influences on Dvořák’s Concerto was the Concerto no. 2 by Victor Herbert, a work he heard performed by Herbert himself in New York. Dvořák also admired the work of two other cellists—the American Alwin Schroeder in Boston and the Czech Hanuš Wihan, to whom the Cello Concerto is dedicated. Dvořák, upon his return to Prague, presented the work to Wihan. The virtuoso was dissatisfied with many aspects of the work and suggested numerous revisions including the interpolation of a cadenza near the end of the finale. The composer rejected nearly all of these. One important revision, however, stemmed from the composer himself. In 1865 the composer became the piano teacher for two sisters, Josefina and Anna Čermáková, the latter of whom was to become Dvořák’s wife. Indeed, the composer in that year penned a Concerto for Cello and Piano in A for his colleague Ludevít Peer. His sister-in-law Josefina became especially fond of one of Dvořák’s songs composed in the winter of 1887-88, Lasst mich allein (“Leave me alone”), op. 82, no. 1. When she fell gravely ill during the composition of the Cello Concerto, Dvořák decided to include a quotation of the melody of the song in the second movement. Upon her death in May 1895, he added a reminiscence of the tune in the finale as well (played by a solo violin), adding a moving personal touch to the work. The Cello Concerto received its first performance in London on March 19, 1896, with Leo Stern as soloist. A letter of protest from the composer, written in English, survives in which he argues for the engagement of Wihan to perform it.

Although the work is scored for large orchestra, Dvořák succeeds in never obscuring the soloist. Intense drama, soaring lyricism, virtuosity, and adventuresome harmonic episodes live happily side by side, with no one element overshadowing the others. The essential unity of the three movements is strengthened by the use of thematic recall (cyclic techniques). One of the most memorable modern performances of the work took place in London during the spring of 1968 when the Russian virtuoso, Mstislav Rostropovich, was engaged to play it in the aftermath of the incursion of Soviet tanks in the streets the Czech capital city during the historic “Prague Spring.” Shouts came from the audience as the master took his seat—“Play it for the Czechs!” By all accounts, it was a performance for the ages.

Program Note by David B. Levy, © 2004/2014/2024

Johannes Brahms was born on May 7, 1833 in Hamburg and died in Vienna on April 3, 1897. One of the dominant composers of the late nineteenth century, Brahms greatly enriched the repertory for piano, organ, chamber music, chorus, and orchestra. His Symphony no. 2 was composed in 1877 and was first performed in Vienna on December 30 of that year under the direction of Hans Richter. The work is scored for 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, and strings. The Winston-Salem Symphony’s most recent performances of this work occurred in March 2009, with JoAnn Falletta conducting.

Brahms, after considerable trepidation, completed his Symphony no. 1 in 1876. Ever conscious of Beethoven’s long shadow, Brahms delayed writing a symphony until he felt that his craft was equal to the challenge. His Symphony no. 1 stands, so to speak, toe to toe with his great predecessor. One needn’t search far for Beethovenian influences, especially those stemming from the titan’s imposing minor-key masterpieces, the Fifth and Ninth.

Once Brahms had overcome his anxiety of Beethovenian influence, he did not wait long to write another symphony. He penned his Symphony no. 2 during the summer of 1877, with most of the work on it taking place in the idyllic Carinthian resort town of Pörtschach, near the Wörthersee. Its first performance took place in Vienna on December 30 with the Vienna Philharmonic under the direction of Hans Richter. The composer, in one of his whimsies of self-deprecation, apologized for the small scale of work. Such protestations, of course, were totally unnecessary, as the work’s proportions certainly have been found to be large enough for most serious music lovers. Its good humor and geniality, however, do set the Symphony no. 2 apart from its three sisters, making it the most easily approachable of the four. The Vienna critics certainly found it to be so, with the audience demanding a repeat of the third movement. Everyone who knew Brahms recognized that the work could only have been conceived amidst the beauty of nature, as opposed to the relative squalor of the city. It is a work filled with sunshine, but one that is often tinged with typically Brahmsian melancholic nostalgia.

The opening Allegro non troppo is one of the most tightly structured movements in the symphonic repertory. Most of its material is derived from a three-note motive—D, C#, D—first heard in the cellos and basses in the opening measure. Much of the other thematic material used throughout the movement is derived from the arpeggiated figure sounded in following two measures. In point of fact, these two primary ideas permeate not only the first movement, but, in subtle ways, the entirety of the work. The lyrical theme that dominates the second key area (F# Minor/A Major) surely reflects Brahms’s indebtedness to Franz Schubert. This tune, sung by the violas and cellos, comes straight from the world of Schubert’s two-cello String Quintet, D. 956. The point of highest drama in this first movement occurs in the development section, when the three-note motive is subjected to strenuous overlapping counterpoint, resulting in some momentary glancing dissonances in the trombones. The recapitulation is crowned with a nostalgic coda, toward the end of which Brahms makes clear reference to one of his own songs: Es liebt sich so lieblich im Lenze! (“Love is so Lovely in Spring “), op. 71, no. 1. All drama subsides as the movement comes to a wistful conclusion.

Rich harmonies, dark sonorities, and a cantabile cello line set an expansive mood for the second movement, Adagio non troppo. Its structure is a three part design, the contrasting middle section changing from 4/4 meter to 12/8 (L’istesso tempo, ma grazioso). This shift adumbrates the seventh variation (also grazioso) from Brahms’s Variations on a Theme of Haydn, Op. 56a (1873). The third movement is in five brief parts, which on the surface would qualify it as a rondo (ABACA), but the second and fourth sections are variants of the first part, implying that a theme and variation form also is at work here. It begins Allegretto grazioso (Quasi Andantino) with a gentle 3/4 oboe tune which is punctuated with gentle grace notes and a shift from major to minor modality. Soon a Presto ma non assai, 2/4 begins lightly in the strings—a reminder that this movement is, after all, a scherzo and not a minuet. The original tempo and oboe tune return, but with new touches in its orchestration. The fourth section, Presto ma non assai, 3/8, is the most explosive part of the movement, but it eventually yields to the original tempo. Brahms offers some harmonic surprises toward the end, but nothing in this gentle movement could possibly offend even the most sensitive ear.

Fun is not a word that one usually associates with Brahms, but how else could one characterize the joyous finale? Donald Francis Tovey called this movement the “great-grandson” of Haydn’s Symphony no. 104 (also in D Major). He may well have considered it to be the “grandson” of Beethoven’s Second Symphony it, too, cast in the same key). Even the movement’s most lyrical episodes fail to escape the infectious good spirits of its opening theme, played at first sotto voce by the strings alone. The explosive good humor will not be suppressed for long, however, and the full orchestra soon bursts forth with great vigor.

A clue to the success of this symphony is the fact that it never draws attention to its highly complex design. Performers and listeners alike should be grateful that Brahms, commonly known for his serious demeanor, for once at least, could enjoy a broad smile. And so should we.

Program Note by David B. Levy © 2008/2021/2024

George Gershwin was born in Brooklyn, NY on September 26, 1898 and died in Hollywood, CA on July 11, 1937. While his career began as a song plugger in New York City’s Tin Pan Alley, he went on to great success on Broadway in the concert hall. His most important stage work was the opera, Porgy and Bess, which remains in the repertory of opera companies and which enjoys occasional revivals on Broadway. Rhapsody in Blue was composed in 1924, the same year in which he wrote his Concerto in F to fulfill a commission by the band leader, Paul Whiteman. This year marks the work’s centennial. The original orchestra (“theater orchestra”) was made by Ferde Grofé. The full orchestra version appeared in print in 1942. The “original” version had its premiere on February 12, 1924 in New York City’s Aeolian Hall, with Whiteman leading his band and the composer serving as soloist. The full orchestral version is scored for 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 2 alto saxophones, tenor saxophone, 3 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, banjo, and strings. The Winston-Salem Symphony most recently performed Rhapsody in Blue with pianist Tamir Hendelman on a May 2014 program conducted by Robert Moody.

A trill on a low F in the clarinet is followed by a seventeen-note rising scale in the key of B-flat major. Ross Gorman, the clarinetist in Paul Whiteman’s band, however, either by accident or on purpose, turned the upper part of the scale into a slow and sexy glissando, thus creating one of the most famous openings in the entire history of music. Accident or no, the composer loved it and it has remained indelibly stamped on the imagination as the signal of Americana in the “Roaring ‘20s.” Popular culture took over almost immediately, and who among us can now separate Rhapsody in Blue from one of America’s largest airlines?

George Gershwin was already a rising star in the musical world when Paul Whiteman, encouraged by an earlier attempt to bring together classical music and jazz on the same program, approached the young composer to produce a concerto-like piece. Whiteman had been impressed by Gershwin when the two collaborated in the Scandals of 1922. After first refusing the commission, Gershwin relented and agreed to contribute to Whiteman’s “experimental concert.” The composer gives us a glimpse of what was on his mind in an explanation given in 1931 to his biographer, Isaac Goldberg:

It was on the train [to Boston], with its steely rhythms, its rattle-ty bang, that is so often so stimulating to a composer—I frequently hear music in the very heart of noise. . . . And there I suddenly heard, and even saw on paper—the complete construction of the Rhapsody, from beginning to end. No new themes came to me, but I worked on the thematic material already in my mind and tried to conceive the composition as a whole. I heard it as a sort of musical kaleidoscope of America, of our vast melting pot, of our unduplicated national pep, of our metropolitan madness. By the time I reached Boston I had a definite plot of the piece, as distinguished from its actual substance.

Gershwin’s original title for the work was “American Rhapsody,” but was changed at the suggestion of his brother, Ira. While chastised by “serious” newspaper critics as lacking in form, the work became popular with audiences almost immediately. The premiere of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue on February 12, 1924 in New York’s Aeolian Hall was an event that attracted attention from Tin Pan Alley to Carnegie Hall. Representatives of the latter venue who attended the concert were violinists Fritz Kreisler, Mischa Elman, and Jascha Heifetz. Sergei Rachmaninoff was there, as were conductors Wilem Mengelberg, Leopold Stokowski, and Walter Damrosch. The latter figure was so taken with the work that he offered Gershwin a commission for a concerto for piano and orchestra.

Program Note by David B. Levy, © 2013/2022/2024

Richard Strauss’s operatic masterpiece, Der Rosenkavalier (The Chevalier of the Rose) was first performed on January 26, 1911 at the Hofoper in Dresden. Capitalizing on the opera’s success, the composer later arranged two “Waltz sequences” containing music derived from Acts I and II, and Act III, respectively. These orchestral pieces have taken on a life of their own in the concert hall. The Suite from Der Rosenkavalier is scored for piccolo, 2 flutes,2 oboes, English horn, 4 clarinets (including E-flat clarinet and bass clarinet), 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, celesta and strings. The Winston-Salem Symphony’s most recent performances of the Suite from Der Rosenkavalier took place in January 2015 with Robert Moody conducting.

Der Rosenkavalier may be seen as a sentimental glimpse back to an eighteenth-century Vienna that never really existed. Indeed, its late-romantic musical vocabulary and use of waltzes are charmingly anachronistic. Strauss uses a wonderful libretto by the great Austrian playwright and poet, Hugo von Hofmannthal, to give musical expression to a super-charged eroticism free from the more disturbing sexuality and violence of his earlier scandalous operas, Salomė and Elektra. Der Rosenkavalier is set in the Vienna of Habsburg monarch, Maria Theresia (reigned 1740-80). To make short work of a rather complicated plot, the story centers on a young nobleman, Octavian, the lover of the Marschallin (wife of the Field Marshall). When the Marschallin is asked by her oafish and lascivious cousin, Baron Ochs, to find a representative to present a silver rose as a wedding offering to his young and innocent fiancée, Sophie von Faninal, she gives the job to Octavian, who promptly falls in love with Sophie. The opera ends happily for the young lovers and wistfully for the wise and aging Marschallin.

Among the music that Strauss extracted from his three-act opera for the Suite from Der Rosenkavalier is the exciting and sensuous opening sequence from Act I, depicting the rapturous lovemaking of Octavian and the Marschallin. The music from near the start of Act II, featuring the solo oboe, accompanies Octavian’s presentation of the silver rose to Sophie. This music’s piquancy derives in part from an ethereal sequence of chords in the flutes, celesta, and harp interpolated as the theme unfolds. This is followed by a waltz sequence based upon a tune sung by the vain Baron Ochs, “Ohne mich . . . mit Mir,” that dominates the end of Act II. Strauss also interpolates an Italianate aria for tenor, which is sung during the Marschallin’s morning toilette in Act I. The final music from the Suite is derived comes from the trio and duet (“Is it a dream, can it truly be?”) that ends the opera. The magical harmonies from the presentation of the silver rose punctuate the cadences of this heavenly love duet.

Program Note by David B. Levy © 2014/2024

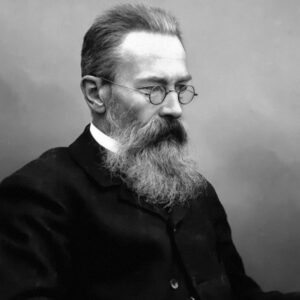

The Russian master, Nicolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov, was born in Tikhvin, March 18, 1844 and died in Lyubensk, near Luga (now Pskov district), on June 21, 1908. He was a brilliant composer, arranger, and teacher, whose illustrious students included Igor Stravinsky. A member of the group of composers known as “The Five,” Rimsky-Korsakov (along with Mussorgsky, Balakirev, Cui, and Borodin) played an important role in developing an idiosyncratic Russian musical voice. The author of a manual on orchestration, and prized by all as a master of the same, Rimsky-Korsakov is best known for his orchestral showpieces, including the Great Russian Easter Festival Overture, Capriccio Espagnol, and the most popular of them all, Scheherazade (1887-8). The work was first performed on November 3, 1888 in St. Petersburg and is scored for piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes (one doubling on English horn), 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 French horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, and strings. The Winston-Salem Symphony’s most recent performances of Scheherazade occurred in January 2011.

Composed in 1888, the symphonic suite in four movements based on tales from the Thousand and One Nights, Scheherazade has captured the imagination of audiences, as well as serving as a model of orchestral opulence and virtuosity. The reasons for its immense and popularity are readily apparent. Scheherazade is filled with sumptuous and tuneful melodies, brilliant splashes of orchestral color, exoticism of subject, and enough virtuoso writing to please everyone. This work has spawned other masterpieces, most notably Stravinsky’s ballets, The Firebird and Petrouchka (Stravinsky was Rimsky’s pupil) and Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloe. None of these scores could ever have existed without Rimsky’s model. The “plot” of Scheherazade’s story is given in the score:

The Sultan Schahriar, persuaded of the falseness and the faithlessness of women, has sworn to put to death each one of his wives after the first night. But the Sultana Scheherazade saved her life by interesting him in tales she told him during one thousand and one nights. Pricked by curiosity, the Sultan put off his wife’s execution from day to day, and at last gave up entirely his bloody plan.

A sense of narrative is apparent everywhere in the piece. A solo violin serves as the voice of the Sultana. Listeners should be content to give their imaginations free reign regarding the details of each tale, since even the titles for each of the movements were afterthoughts, urged on the composer by his friends.

Program Note by David B. Levy

American composer, pianist, conductor, and author Matthew Aucoin was born in Natick, MA near Boston on April 4, 1990. His eclectic musical education included performing in the indie rock band, Elephantom, followed by a degree in poetry from Harvard (2012), where he also conducted operatic productions and continued to develop his ideas as a composer of opera. He pursued a graduate diploma in composition from Juilliard (2014), where his principal teacher was Robert Beaser. This course of study was followed by a period as an Assistant Conductor at the Metropolitan Opera and as the Solti Conducting Apprentice at the Chicago Symphony, where he studied with Riccardo Muti. Although he has composed music in numerous genres and has worked with many of the greatest performers, ensembles, and conductors, his greatest fame lies in the world of opera. His Eurydice, co-written with librettist Sarah Ruhl, was commissioned jointly by the Metropolitan Opera and the Los Angeles Opera and it had its world premiere in Los Angeles in February 2020, followed by its Met premiere in November 2021, conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin. This opera interprets the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice—itself the subject of some of the most important operas in history, dating from the early 17th century—from the perspective of the female character, Eurydice, who is fatally bitten by a serpent on her wedding day. A joint commission from the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Winston-Salem Symphony, and the Harvard-Radcliffe orchestra led to Aucoin’s creation of an eighteen-minute suite from the opera, which received its first performance by the Philadelphia Orchestra on February 3, 2022. It is scored for 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 3 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, percussion, 2 harps, piano, and strings.

The composer has written the following notes about his Eurydice Suite:

The Eurydice Suite is an orchestral condensation of my opera Eurydice, which is based on Sarah Ruhl’s surreal and heartbreaking play. Like the opera, the suite begins with an unsettling sound: the metallic “ping” of oblivion that announces the passage of the newly-dead through the river of forgetfulness. And like the opera, the suite toggles between the world of the living and the subterranean realm of the dead.

The suite’s first movement is a tour of the underworld: its watery percussion sounds, its “strange high-pitched noises, like a tea kettle always boiling over.” Near the end of the movement, we hear a strange sound from the contemporary world: the keening wail of a New York subway train pulling out of a station. Eurydice, newly arrived in death, hallucinates that she is alone on some unknown train platform, waiting for someone—she can’t quite remember who—to meet her.

The second movement pays a visit [to] the world above, where Orpheus (in the guise of a solo clarinet) mourns luxuriantly. He drops a letter into the earth, hoping it will reach the underworld; and as his music fades away, we return down below, where Eurydice’s father patiently builds her a room out of string. In the third movement, the string section embodies the slow weaving of that delicate room.

The fourth movement is a phantasmagorical montage of the opera’s final act: the disastrous walk toward the world above, and the many missed connections that lead to every character being dipped once again in the river of forgetfulness.

Program Note by David B. Levy/Matthew Aucoin, © 2023

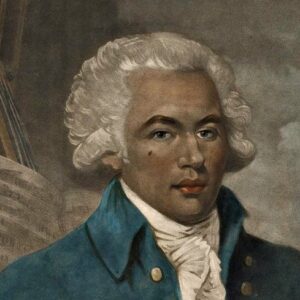

Composer and violinist Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges was born in Baillif, Guadeloupe on December 25, 1745 and died in Paris, June 9, 1799. He is one of 18th-century music history’s most intriguing figures, long known mainly to music historians but relatively unknown to audiences until recently. Interest in composers of color has led to world-wide renewed interest in his life and music, both of which have allowed his music to emerge from the relative, and undeserved, obscurity. As a result, audiences are discovering not only a fresh musical voice from the past, but research has restored Bologne’s reputation as a master of many skills, including his fame as a champion fencing master. Indeed, no less a figure than John Adams, who encountered Bologne in Paris, judged him to be the “most accomplished man in Europe.” His Symphony no. 2 in D Major is in three movements and dates, as best as we can tell, from the 1770s. Also known for his operas, the L’amant Anonyme (The Anonymous Lover) dates from 1780 and is the only one of Bologne’s six operas to have survived. Its overture is a reworking of his Symphony no. 2 in D Major, dating from the 1770s. It is scored for 2 oboes, 2 horns, and strings.

As a graduate student in musicology, the name of Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges was brought to my attention by Professor Barry Brook of the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. Brook, whose expertise was in 18th-century music, shared with me and my fellow aspiring musicologists the importance of this composer in the development of the genre known as the symphonie concertante; a cross between symphony and concerto for two or more instruments. This type of composition was especially popular in Paris, but fine examples stemmed from the pens of Haydn, Mozart, and others.

Bologne was the son of a white planter, George Bologne, and his African slave Nanon. The title Chevalier de Saint-Georges became official when his father acquired the title of Gentilhomme ordinaire de la Chambre du Roi. The family resettled in France in 1753, after which Joseph began his tutelage as a champion swordsman, leading eventually to his earning the title of Gendarme de la Garde du Roi as well as the title of Chevalier. After George Bologne returned to Guadeloupe, Joseph, who became the beneficiary of an annuity created by his father, remained in France, becoming the darling of the elite, partly based on his expertise as a fencing master. The great American diplomat John Adams dubbed him as “the most accomplished man in Europe in riding, shooting, dancing, fencing, and music.”

Much less is known of his early musical training, although evidence suggests he was already known in musical circles as early as early as 1764, based largely on his skill as a violinist and composer. He soon became the leader (concertmaster) of a new orchestra, the Concerts des Amateurs. This opportunity led to his composition of two concertos for violin which demonstrated his extraordinary skills as a virtuoso. Under his guidance, the Orchestra of the Amateurs became one of Europe’s leading ensembles.

His success led in 1776 to a proposal that Joseph be named director of the Paris Opéra, but racism reared its ugly head as a faction petitioned Queen Marie Antionette, refusing to be governed by a mulatto. Louis XVI decided to nationalize the institution, thus blunting Saint-Georges’ critics. As a result, the composer turned his attention increasingly toward the composition of operas. But by the 1780s, he again took up the mantle of orchestra leader and founded the Concert de la Loge Olympique, the organization that commissioned the illustrious Joseph Haydn to compose his six “Paris” Symphonies (nos. 82-87). While music, opera, and fencing remained central to Saint-Georges’ life, he also became a strong advocate for equality for black people in France and England. He thus was, and once again has become, a symbol for racial equality. A man of myriad talents once again is receiving richly deserved recognition as an important cultural figure.

The Overture to his opera, “L’amant anonyme” uses the same music as his Symphony no. 2, a cheerful work in three movements played without pause. The outer movements are exuberant representatives of the popular galant style of the Classical era, while the central slow movement, a rondo in the minor mode, adds a touch of pathos. The three-part structure is the same one found in 18th-century overtures in the Italian style. Such works were often identified as “Sinfonia,” and were among the forms that contributed to the evolution of the symphony.

Program Note by David B. Levy, ©2022/2023

Thank you for caring to make a commitment to bring music to life in our growing community. Your pledge of support will enable us to reach new and existing audiences with concert and educational experiences here in Winston-Salem and beyond.

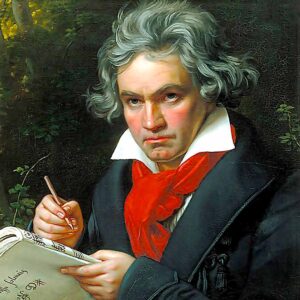

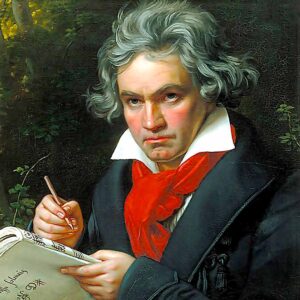

One of history’s pivotal composers, Ludwig van Beethoven was born on December 16 or 17, 1770 in Bonn, and died in Vienna on March 26, 1827. His Ninth Symphony, op. 125 was composed over a period of many years, most intensely between 1822 and 1824, culminating in its premiere in Vienna’s Kärtnertortheater on May 7, 1824. It is scored for piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, triangle, bass drum, cymbals, timpani, and strings. The Winston-Salem Symphony’s most recent performances of this work occurred in October 2016.

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony has acquired a status of universal approbation unmatched in the symphonic repertory. The British affectionately call Beethoven’s Ninth the “Choral” Symphony, while the Japanese, who each December present well over one hundred performances of it, have dubbed the work “Daiku” (“Big Nine”). It is a mainstay of concert halls and music festivals throughout the world. Wagner saw fit to conduct a performance of it when he laid the cornerstone of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus in 1872. In the summer of 1989 in China, revolutionary students gathered in Tiananmen Square and played its finale through loudspeakers in order to bolster their spirits. Later the same year, in Berlin, Leonard Bernstein led a ceremonious performance of it, changing Schiller’s “Freude” (Joy) to “Freiheit” (Freedom) in symbolic celebration of the razing of the Wall which had divided that city.

The Ninth is, at the same time, one of Beethoven’s most perplexing

compositions—a work that remains one of the world’s most revered musical masterpieces, but which is not without its problematic side. Its musical syntax is a curious mixture of complexity and simplicity, and over time critics have seen fit to assail it on both counts, although virtually no composer after Beethoven could escape the Ninth’s immense shadow. Stemming as it did from a particular time and circumstance—Vienna during the during the age of Metternich—with all the musical, social, and cultural associations of that period, the Ninth Symphony has emerged as a ceremonial piece par excellence, befitting artistic and political summitry, as well as a populist symbol for freedom-loving citizens from Beijing to Berlin. The Ninth Symphony is much more than a monument of Western music: it is a cultural icon. UNESCO declared it to be the first musical composition to be entered into the Memory of the World Register in 2001.

Beethoven’s last symphony represents the culmination of two discrete projects. The first was the fulfillment of a commission for a new symphony tendered by the Philharmonic Society of London in 1822, itself the partial satisfaction of an earlier request from the Society for two new symphonies. The other project dates back to 1792, the year in which we have the first evidence of Beethoven’s interest in setting Friedrich Schiller’s 1785 poem, An die Freude (Ode to Joy), to music. The joining of these separate enterprises into the Ninth Symphony did not occur until relatively late in the symphony’s evolution. First performed in Vienna on 7 May 1824, the Ninth Symphony immediately made a tremendous impact, despite its faulty execution.

Indeed, the work itself seems immeasurable. The opening Allegro un poco maestoso is far from the longest first movement that Beethoven wrote, yet its scale is greater than any other. One reason for this lies in the density of its content. From a barely audible murmur, fragments in the strings grow in speed and intensity as they coalesce to form the titanic first theme. The time scale in which this occurs is small, but its implication is immense. Never before, and rarely since, has such force ever been unleashed in music. The opening of the movement is unique, yet all subsequent imitations of it (Bruckner and Wagner, most notably) were conceived in fully self-conscious homage to Beethoven. Equally cataclysmic in its impact is the explosion in D major that launches the movement’s recapitulation. The powerful funereal peroration from the coda also has also been imitated—most notably by Gustav Mahler—but never equaled. The first movement of the Ninth Symphony is tragedy writ large.

The scherzo, which is placed as the symphony’s second movement, offers little relief. Tragedy is now re-played as farce as the strings and kettledrums hammer out its distinctive motif. After a full-scale treatment of the Molto vivace in sonata form, replete with a fugal exposition and metrical trickery in its development section, the pastoral trio in D major offers the first true moment of respite. The word scherzo means joke, but anyone familiar with Beethoven know that his humor often has its dark side, and the scherzo of the Ninth Symphony is one of the demonic ever penned. The final “joke” of this movement comes in its coda, where Beethoven threatens to repeat the trio section, only to thwart our expectation with an abrupt ending—a gesture that he used in the scherzo of his Seventh Symphony (1812).

The Adagio molto e cantabile third movement dwells in the realm of pure melody and dance. Aestheticians in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were fond of making a distinction between the “sublime” (lofty) and the “beautiful” in art. If the first two movements are representative of the former, the third movement of the Ninth Symphony surely is an exemplar of the latter. The movement is cast as a rondo with varied reprises for each of its two themes. A distinguishing characteristic of the first theme is the woodwind echo that occurs at the end of each phrase of the hymnal theme played by the strings, a feature that is retained in each of its returns. The second theme is a contrasting Andante moderato in triple meter. The literal midpoint of the movement (and, in fact, the entire symphony) is its ethereally calm development section, where the color of woodwinds (Harmoniemusik) dominates its landscape. The fourth horn emerges out of this heavenly serenity in a celebrated passage which culminates in an unaccompanied scale. Listeners should attend to how this instrument continues to play a prominent, and often virtuosic, role throughout the remainder of the movement.

The onset of the finale rudely shatters the calm with a glancing dissonance and a passage that Wagner dubbed the “horror fanfare” (Schreckensfanfare). Evidence from Beethoven’s sketches reveal that Beethoven had considerable difficulty effecting a transition from the purely instrumental opening movements to the choral part of the finale. How, after all, does one introduce an element that never before had belonged to a genre? Using every bit of his ingenuity, and bringing his experience gained from previous works to bear (the “Choral” Fantasy and several piano sonatas), Beethoven hit upon the idea of using instrumental recitative—played here by the cellos and contrabasses—as a conduit from the world of purely instrumental music to that of instrumental/vocal.

The instrumental recitative is a superbly effective device, used as a link between fragmented reminiscences from the previous movements. The reason for these thematic recollections has been interpreted by analysts in various ways. Most writers suggest that the recitative serves as a rebuff of the spirit of these earlier movements, each of which in turn is spurned by the cellos and basses until the famous “Joy” melody is presented. But there is another possible reason why Beethoven elected to bring back these themes, a purpose that is as much prospective as it is retrospective. The elaborate multi-sectional finale plays out as an entire four-movement symphonic structure in miniature. Viewed from this perspective, the episode of recitative and recollection is an introductory prefiguration of the landscape of the entire finale.

The presentation of the “Joy” theme in variations (both instrumental and vocal) comprises the gesture of a first “movement.” The portions of Schiller’s An die Freude used in this part are the ones that are most overtly profane or pagan in spirit. This is followed by the “Turkish” music that acts as a kind of scherzo, which in turn yields to a solemn slow “movement” (Seid umschlungen, Millionen). This third section devotes itself to the most overtly sacred parts of Schiller’s poem. The re-entry of the “Turkish” percussion movements marks the onset of the “finale,” where Beethoven joins together the profane and the sacred in a symbolic marriage of Athens and Jerusalem. Joy, then, serves as the agent through which “all men become brothers.”

Notes by David B. Levy © 2008/2016/2019/2022

American composer Carlos Simon was born in 1986 in Washington, DC. The son of a preacher, he was raised on a mix of the improvisatory nature of Gospel music and the more formal structural elements found in Classical music. His formal musical studies were pursued at Morehouse College, Georgia State University, and the University of Michigan. Among his teachers at Michigan were Michael Daugherty and Evan Chambers. As a music educator, Simon has served on the music faculties at Spelman College and Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia. He currently serves as Assistant Professor at Georgetown University. In 2021 the Sphinx Organization awarded him the Medal of Excellence, and he has been Composer-in-Residence for the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. Simon was nominated for a 2023 GRAMMY Award for Best Contemporary Classical Composition for his album, Requiem for the Enslaved. His five-minute-long orchestral composition, Fate Now Conquers, received its first performance on March 26, 2020 at Philadelphia’s Kimmel Center under the direction of Yannick Nézet-Séguin. Since its premiere, it has been performed widely throughout the United States. The work is scored for Flute, 2 oboes, 2 Clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings.

The inspiration for Fate Now Conquers comes from an entry in Ludwig van Beethoven’s Tagebuch, a diary that he kept from the years 1812-1818. Although Beethoven’s formal education was sporadic, he prided himself on reading as much ancient and contemporary literature and philosophy available to him. We know that Homer was among the ancients with whom he was familiar because of two entries, one each from the Iliad and the Odyssey. Beethoven lamented that his familiarity with some authors was limited to translations. The reference fate in the Tagebuch, interestingly contains metrical scansions, indicating perhaps that he may have considered setting the quotation from the Iliad to music. Carlos Simon wrote of his Fate Now Conquers:

This piece was inspired by a journal entry from Ludwig van Beethoven’s notebook, written in 1815:

Iliad. The Twenty-Second Book:

But Fate now conquers; I am hers; and yet not she shall share in my renown; that life is left to every noble spirit and that some great deed shall beget that all lives shall inherit.

Using the beautifully fluid harmonic structure of the second movement of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, I have composed musical gestures that are representative of the unpredictable ways of fate. Jolting stabs, coupled with an agitated groove with every persona. Frenzied arpeggios in the strings that morph into an ambiguous cloud of free-flowing running passages depict the uncertainty of life that hovers over us.

We know that Beethoven strived to overcome many obstacles in his life and documented his aspirations to prevail despite his ailments. Whatever the specific reason for including this particularly profound passage from the Iliad, in the end, it seems that Beethoven relinquished himself to fate. Fate now conquers.

Those familiar with the Allegretto from Beethoven’s Symphony no. 7 will be hard pressed to hear actually how its “fluid harmonic structure” is articulated in Fate Now Conquers. Nevertheless, the Beethovenian idea of “seizing fate by the throat” and the struggle it represents come through clearly, perhaps representing for Carlos Simon, the social struggles that perplex our own society, as well as the hope of overcoming adversity in all its manifestations.

Program Note by David B. Levy/Carlos Simon, © 2023

One of history’s pivotal composers, Ludwig van Beethoven was born on December 15 or 16, 1770 in Bonn, and died in Vienna on March 26, 1827. Of the four overtures associated with his only opera, Fidelio (originally entitled Leonore), the Leonore Overture no. 3 was composed in 1805-6 for its first revision. Its first performance took place on 29 March 1806, in Vienna’s Theater an der Wien. The vocal quartet,“Mir ist so wunderbar,” occurs in Act I of the opera. The overture is scored for 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, and strings. The Winston-Salem Symphony first performed the overture in October 1959; its most recent performances took place in September 2012. These mark the first Symphony performances of the Act 1 quartet.

Leonore, ou L’amour conjugal is the title of a rescue drama written by the French playwright, Jean Nicolas Bouilly. The play would attract little attention nowadays were it not for the fact that Beethoven based his only opera, Fidelio (originally entitled Leonore), upon it. The play, originally set against the backdrop of the French revolution of 1789, is filled with the virtues of love, loyalty, and political freedom that were ever near and dear to the composer’s heart.

Fidelio exists in three versions, and Beethoven composed no fewer than four separate overtures for it. The original version was first produced in Vienna’s Theater an der Wien on November 20, 1805 under the worst possible circumstances. Beethoven not only had to deal with a weak libretto by Joseph Sonnleithner, but the occupation of the Austrian capital by Napoleon’s Grand Army only days earlier made the Viennese citizenry too frightened to leave home, let alone to attend the theater. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that the enterprise failed miserably.

The overture used for this earliest version of the opera is now known, oddly, as Leonore Overture no. 2. What is now referred to as the Leonore Overture no. 1 was composed in 1806-7 for a projected performance of Fidelio in Prague. The performance never took place, however, and this overture was never performed during Beethoven’s lifetime.

When Beethoven revised Fidelio in 1805-6, with improvements to the libretto provided by his friend Stephan von Breuning, he composed the Leonore Overture no. 3. This work has many elements in common with the opera’s original overture, now known as the Leonore Overture no. 2—including off-stage trumpet calls—and it still was intended to be played before the opera begins. When Beethoven made his final revisions to the opera in 1814, he wrote an entirely new overture, known as the Fidelio Overture. This new overture, however, raised a dilemma for those conductors who wish to use the musically superior Leonore Overture no. 3 within the context of the opera. Some conductors choose to perform it at the beginning of Act II. Others opt to place it at some point after the dungeon scene of Act II—the climactic moment when Leonore, disguised as the assistant jailer, Fidelio, rescues her unjustly imprisoned husband, Florestan, from murder at the hands of the evil and ambitious minister, Pizarro. The trouble with the first option is that the dramatic events of the scenes that follow are rendered dramatically redundant. The problem with placing the overture after the rescue scene is that the overture loses its impact, the audience having already experienced the very events that the overture exhibits in purely musical sounds. When performed as a concert piece, as it is on this program, however, none of these issues are of concern.

The overture’s introduction, after its suspenseful opening descriptive of Florestan’s dark subterranean prison cell, develops material derived from his introductory aria in Act II, “In des Lebens Frühlingstagen” (“In the Springtime of Life”), where the prisoner reflects on the justness of his cause and hope for liberation. Most of the music of the main body of the sonata-form overture is based upon material not used in the opera itself, but it captures its heroic spirit admirably. The trumpet calls that announce the arrival of Don Fernando, the king’s minister, in the opera are placed at the moment of greatest musical tension for a piece cast in sonata-form—near the end of the development section. A wonderful element in the recapitulation is the addition of virtuosic writing for the principal flute and bassoon. The overture ends with an appropriately heroic coda that is similar to the one that ends the finale of his Symphony no. 3 (Eroica). The Leonore Overture no. 3 offers further confirmation of Beethoven’s genius as the unsurpassed master of dramatic expression through purely instrumental means.

The vocal quartet from Act I of Fidelio, “Mir ist so wunderbar” (I feel so strange), is a wonderful example of how four different characters (Marzelline, Fidelio, Rocco, and Jacquino) can express completely different emotional states while singing the same music. It begins with soft and profoundly moving introduction in the lower strings of the orchestra, followed by the singers each singing the same melody in the form of a round (or canon). The first character we hear is Marzelline, daughter of the jailer, Rocco. She believes that Fidelio (Leonore disguised as a young man) is in love with her. Recognizing this, Leonore/Fidelio comments on how precarious a moment this is. The affable jailor, Rocco, comments that Fidelio and Marzelline would make a fine couple, while Jacquino, Rocco’s assistant jailor who is in love with Marzelline, expresses his frustration and jealous anger over the situation.

While each of the singers carries the same tune, Beethoven expertly changes the orchestral accompaniment in the woodwinds to reflect the emotional state of each character. After each of the four characters make their entrance, the strings add a new and tender layer of sonority to the mix. The end result is one of the greatest glories of vocal ensemble writing ever created.

TEXT

Marzelline

I’m feeling so strange,

My heart feels so tight;

He loves me, that is clear,

How happy I shall be!

Leonore

How great is the danger!

How faint the ray of hope!

She loves me, that is clear,

O unspeakable pain!

Rocco

She loves him, that is clear;

Yes, my girl, he shall be yours!

A fine young couple;

They will be happy.

Jacquino

My hair stands on end!

Her father concents.

I’m feeling so strange,

There’s nothing I can do!

Program Note by David B. Levy © 2012/2023

The Czech master Antonin Dvořák was born in Nelahozeves, near Kralupy, on September 8, 1841; and died in Prague, May 1, 1904. His “New World” Symphony remains his most popular work. Composed during his residency in the United States in 1892-3, the work received its premiere on December16, 1893 in New York’s Carnegie Hall. It is scored for piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, trumpet, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, and strings. The most recent Winston-Salem Symphony performance of this work is January 2017, under the direction of Robert Moody.

In early 1991, a three-story brick row house at 327 East 17th Street in Manhattan was declared a national landmark. A plaque above the first story declares that this was the New York home from 1892 to 1895 for the famous Czech composer Antonin Dvořák, who composed his Symphony no. 9 (“From the New World”) during a period from January to May 1893. Unfortunately, the brownstone was taken down to make room for the expansion of a nearby hospital and the corner near where it stood was renamed Dvořák Place. The composer moved to New York after Jeannette Thurber invited him to assume the directorate of the National Conservatory of Music. Shortly after taking up residence there, Dvorák communicated the following to a friend in Prague:

“We [the composer, his wife, and two children] live four minutes from my school in a

very pleasant house. Mr. Steinway sent me a piano, free, so we have one good piece of

furniture in the parlor. The rent is $80 a month, a lot for us, but a normal price here.”

Ever since it received its first performance in New York City on December 16, 1893 with Anton Seidl conducting the New York Philharmonic, Dvořák’s “New World” Symphony has remained an extremely popular orchestral work. The Czech master wrote two major works, as well as some smaller ones, during his extended visit to the United States, which included a short summer vacation spent with a colony of Czech immigrants in Spillville, Iowa. One of these compositions was the String Quartet, op. 96 (“American”), the other was this, his last symphony. Had Mrs. Thurber had her way, Dvořák also would have composed an opera based on Longfellow’s story of the Native Americans Minnehaha and Hiawatha, as she hoped that Dvořák would become the founder of a new American “school” of composition. As we shall see, at least some of Mrs. Thurber’s hopes found expression in his “New World” Symphony.

Folk music had always played a vital role in Dvořák’s music, and his “American” efforts serve to remind us that many folk musics have elements in common. The “New World” Symphony speaks its “American” with a distinctly Slavic accent. The title for the work, “From the New World” is the composer’s own, and he explained that it was inspired by “impressions and greetings” from his host country. Among these impressions must be counted the music of African-Americans, whose melodies he learned from one of his students at the Conservatory, Henry Thacker Burleigh. It is difficult to determine just how well-versed Dvořák was in the authentic musical idiom of Native Americans, but the famous Largo movement of the “New World” Symphony, was inspired, according to the composer, by a passage from Longfellow’s “The Song of Hiawatha.” The famous English horn theme of this Largo is still known by many people as a “spiritual” with the words “Goin’ Home.” The Symphony is filled with many such appealing folk-like themes.

Another important element in the “New World” Symphony is its cyclic construction, in which a motto theme, first heard near the beginning of the first movement, is brought back at strategic moments in the subsequent movements. A careful listener will discern that this motto itself is the progenitor of other themes, thereby strengthening the thematic unity of the entire work. Dvořák also provides many masterful moments of orchestration and harmony, none, perhaps, more beautiful than the succession of brass chords at the beginning and end of the Largo.

While the composer was still in America, he sent the manuscript for this symphony to his German publisher Simrock, who in turn showed them to Dvořák’s friend and advisor, Johannes Brahms. Brahms saw fit to make certain corrections, and even some wholesale changes—especially in the finale—where he altered some of Dvořák’s tempos.

Notes by David B. Levy © 2005/2016

Bassist and composer Edgar Meyer was born on November 24, 1960 in Oak Ridge, TN. His extraordinary talent as a soloist, composer, and collaborator has brought him together with a vast array of musical artists, including Joshua Bell, Hilary Hahn, Yo-Yo Ma, Jerry Douglas, Béla Fleck, Zakir Hussain, Sam Bush, James Taylor, Chris Thile, Mike Marshall, Mark O’Connor, Alison Krauss, Mary Chapin Carpenter, Guy Clark, and the trio Nickel Creek. His earliest studies on the bass were with his father, Edgar Meyer, Sr., starting when he was five years old. In 2000, he won the Avery Fisher Prize and in 2002 he was named a MacArthur Fellow. Meyer’s collaboration with Yo-Yo Ma and Mark O’Connor on the widely acclaimed Sony Classical disc Appalachia Waltz brought him a wider audience and greater acclaim than one usually associates with a virtuoso on his instrument. The impressive variety of artists with whom Meyer works gives ample evidence of the breadth of his musical interests and accomplishments. Meyer is also Adjunct Associate Professor of Double Bass at Vanderbilt University‘s Blair School of Music, as well as at the Curtis Institute of Music. He is also an artist-faculty member of the Aspen Music Festival and School. Meyer is the author of three concertos for his instrument. The Concerto no. 1 in D Major was composed in 1993.

The following program notes were written by John Henken for the Los Angeles Philharmonic:

“Most of the music I’ve become interested in is hybrid in its origins,” Meyer says. “Classical music, of course, is unbelievably hybrid. Jazz is an obvious amalgam. Bluegrass comes from 18th-century Scottish and Irish folk music that made contact with the blues. By exploring music, you’re exploring everything.”

Meyer’s Bass Concerto No. 1 was composed in 1993 (he has since written another solo concerto and a Double Concerto for Cello and Bass) at the instigation of Peter Lloyd, principal bass of the Minnesota Orchestra, the ensemble with which Meyer played the premiere, conducted by Edo de Waart.

The opening solo lick, a bluesy upward swagger with an emphatic punctuation, sets the stylistically protean tone for the piece. The orchestra suggests something more ominous, eventually luring the soloist up into chill and glossy heights. The sense of barely stilled worry ends with the understated return of the opening lick.

The middle movement is in the three-part song form typical of classical concertos. In the first section the bass soars lyrically over a pizzicato accompaniment, sounding like a thoroughly acculturated Satie gymnopédie, although Meyer says that he picked up the idea from Haydn’s C-major Violin Concerto. The contrasting central section is agitated and driven, bustling urgently before slipping back into a state of lyric grace, this time with oboe joining the bass in tandem lines.

The finale explodes with fiddling fury, given only more energy by its rooted weight in the bass register, though this too slips its moorings and spins off into instrumental thin air. “I got the idea for this type of tune and the way of playing it from hearing Sam Bush play the violin and mandolin,” the composer says. (Bush was a partner in several projects with Meyer, going back to the 1980s and the newgrass band Strength in Numbers.) Celtic modality, blues engines, suggestions of John Adams in the scoring, and strenuous virtuosity all combine in this movement, also in a three-part form, with a free-floating middle and cadenza.

Program Note by David B. Levy/John Henken (2012), © 2016/2023

String bass virtuoso, composer, and conductor, Giovanni Bottesini was born in Crema, Lombardy on December 22, 1821 and died in Parma on July 7, 1889. His activities as a conductor were important, but he is best remembered for advancing the technique of the string or double bass in the Romantic era. His extraordinary skill as a performer resulted in a significant number of his own compositions for this instrument, including two concertos, chamber works, variations on themes from opera, and a host of assorted works for bass and piano. His Concerto for Contrabass and Orchestra no. 2 is considered one of his finest compositions.

One rarely thinks of the string (double) bass as the featured instrument for a concerto, yet the extraordinarily gifted Giovanni Bottesini has left two such works for posterity. The son of a musician, Bottesini started out as a violinist. His father, recognizing his son’s talent, decided to send him to the Milan Conservatory to further develop his skills, but the family did not have sufficient funds to pay tuition and expenses. As fate would have it, there were scholarships available for bass and bassoon. Amazingly, the young musician was able, after only a few weeks’ practice, to demonstrate enough skill and promise on the bass to gain admittance. A sign of his success was the awarding of a prize of 300 francs, which Bottesini used to purchase a fine instrument made in 1716 by Carlo Giuseppe Testore (the instrument is now in the possession of a private investor in Japan). Thus was launched the career of the “Paganini of the Double Bass.”

Bottesini’s virtuosity as a bassist, however, was not his only calling card. After an extended period of touring as a soloist that took him from Milan to America, Cuba, and England, he became a noted opera conductor in Paris, London, and Italy. His good friend Giuseppe Verdi was sufficiently impressed with Bottesini’s skill as a conductor to have him direct the premiere of his Aida in Cairo on December 27, 1871. Not surprisingly, Bottesini also was the composer of several operas—works that are seldom performed, despite the fact that some of them were well received at their premieres.

While the modern string bass has four strings, in the nineteenth century many performers, including Bottesini used only three, which Bottesini tuned a step higher than normal. This configuration makes the music of his works for the instrument all the more demanding. He also preferred the so-called “French” grip of the bow (overhand grip, as used by the cello, viola, and violin) over the underhand “German” grip. His Concerto no. 2 remains one of the instrument’s most demanding challenges, whose three movements explore the full range of its capability, from rapid passagework to full-throated operatic lyricism. Dramatic fire—as found in the music of his friend Verdi—also are hallmarks of this unusual composition.

Program Note by David B. Levy, 2015/2023

Born in New York City in 1981, African American composer, musician, and educator, Jessie Montgomery is one of the most vital voices of her generation. Her studies began at Manhattan’s Third Street Music School Settlement. She later went on to receive a degree in violin performance at Juilliard and a master’s degree in Composition for Film and Multimedia at New York University (2012). She has been actively involved with the Detroit-based Sphinx Organization in supporting and encouraging young African American and Latinx string instrumentalists. Her works have been performed by many significant arts institutions (Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, American Composers Orchestra, Atlanta Symphony, to name but a few). She also has worked collaboratively with numerous colleagues in both music and dance. Strum began its life as a string quintet in 2006. She later made a string quartet version (2008), reaching its final version in 2012 in celebration of the 15th annual Sphinx Competition.

In her own program notes for Strum, Jessie Montgomery wrote:

Originally conceived for the formation of a cello quintet, the voicing is often spread wide over the ensemble, giving the music an expansive quality of sound. Within Strum I utilized texture motives, layers of rhythmic or harmonic ostinati that string together to form a bed of sound for melodies to weave in and out. The strumming pizzicato serves as a texture motive and the primary driving rhythmic underpinning of the piece. Drawing on American folk idioms and the spirit of dance and movement, the piece has a kind of narrative that begins with fleeting nostalgia and transforms into ecstatic celebration.

Living up to its title, the work uses extensive pizzicato (plucking) effects, evoking the idea of a banjo, over which evocative musical fragments are played (arco) with the bow. In kaleidoscope fashion, the music shifts from idea to idea, keeping the listeners on their toes from start to finish. The work, in its string quartet version, has been recorded by the Catalyst Quartet as part of the album Strum: Music for Strings (2015) on the Azica label.

Program note by David B. Levy/Jessie Montgomery, © 2021/2015

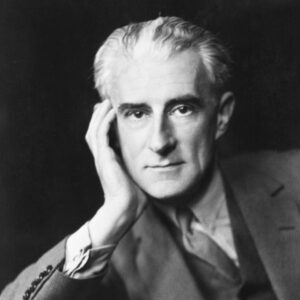

Maurice Ravel was born March 7, 1875 of parents of Swiss and Basque descent in Ciboure, Basses-Pyrénées. He died December 28, 1937 in Paris. La valse had its first performance in Paris with Camille Chevillard conducting the Lamoureux Orchestra on December 12, 1920. It is orchestrated for piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, glockenspiel, 2 harps, and strings. The work was last performed by the Winston-Salem Symphony on January 7, 8, and 10, 1995 with Peter Perret conducting.